Early one Saturday morning in September, Jacob McCleary, then 15, got into his aunt and uncle’s van, headed for the Santa Fe Springs office of the Los Angeles County Department of Children and Family Services (DCFS).

Jacob’s aunt told him they were headed there to fill out some routine paperwork and then they would get ice cream afterward. Without telling him, they had already packed Jacob’s bags.

Jacob had been living as a foster child with his aunt and uncle since age 2, his parents lost to throes of addiction. A dependency court judge had stepped in and placed McCleary and his older brother in their aunt and uncle’s home in Bellflower, a bedroom community on the eastern edge of Los Angeles County’s sprawl.

Life after institutions: Jacob McCleary made it out of the foster care system, where he spent his high school years in a series of residential treatment centers. Photo by Jeremy Loudenback

“It was all ups until 2012,” McCleary said about life until age 12. That’s when he began to experience a series of escalating mental health issues.

McCleary was hospitalized for the first time at age 13, diagnosed with bipolar disorder, and returned three more times over the next couple years for aggressive behaviors related to schizophrenia and what he says doctors described as homicidal behavior.

But on that September day, not long after his 15th birthday, Jacob’s aunt and uncle handed him over to a DCFS social worker, who escorted him to an intensive group home in Riverside County.

Over the next three years, McCleary said he cycled through five different group homes and seven high schools. Just out of the county’s foster care system since November, his memories of his days in care are still fresh.

With a high-level group home, “if you take one step outside the door, you can get slammed on your face because they think you might go AWOL,” McCleary said. “I just came from my home, where I had my pets and my family.”

Stories like McCleary’s — childhoods lost in institutions, years disconnected from family while battling mental health issues and education a blur — are not uncommon among foster youth. But for these young people, who are already managing traumatizing experiences of poverty, abuse and neglect, long-term institutional care can leave lasting scars.

That has prompted an overhaul of how California uses congregate care, a slate of foster care options that includes group homes, residential treatment programs and other institutions like shelters.

The actual number of foster children in group homes has steadily declined in California over the past 15 years. But many foster youth continue to end up living in these institutional settings for long periods of time – sometimes to address mental health needs, and other times because there aren’t enough available foster homes.

In recent years, a much clearer picture of the impact of living in group homes has materialized.

For high school-age foster youth living in group homes, the drop-out rate is 14 percent. In comparison with other peers in foster care, students in group homes are the least likely to graduate high school, matriculating at a rate of 35 percent. Youth with just one placement in a group home were 2.4 times more likely to end up involved with the justice system than other peers in foster care.

Children who spend some time in an institutional facility spend 33 percent longer in foster care than those who live in other foster care placements. Researchers also suggest that an initial placement in an institution like a group home or an emergency shelter lowers the likelihood that a young person will ever reunify with their parents.

California is currently in the midst of an expansive child welfare reform more than a decade in the making. Dubbed “Continuum of Care Reform,” the state is aiming to take some of the hardest to place children out of group homes and help root them in “family-like settings.” Beyond the supposed benefits of keeping young people out of these settings, the move is also projected to be a major money saver — every month a child spends at the most intensive group home costs taxpayers $11,238 a month.

Signed into law by Gov. Jerry Brown (D) in 2015, the reform officially launched in 2017 with several efforts to support foster youth in family homes as much as possible. During that time, the state has pumped more than $600 million into the effort, hoping that limiting the use of group homes would lead to cost savings that could bankroll the foster care reform.

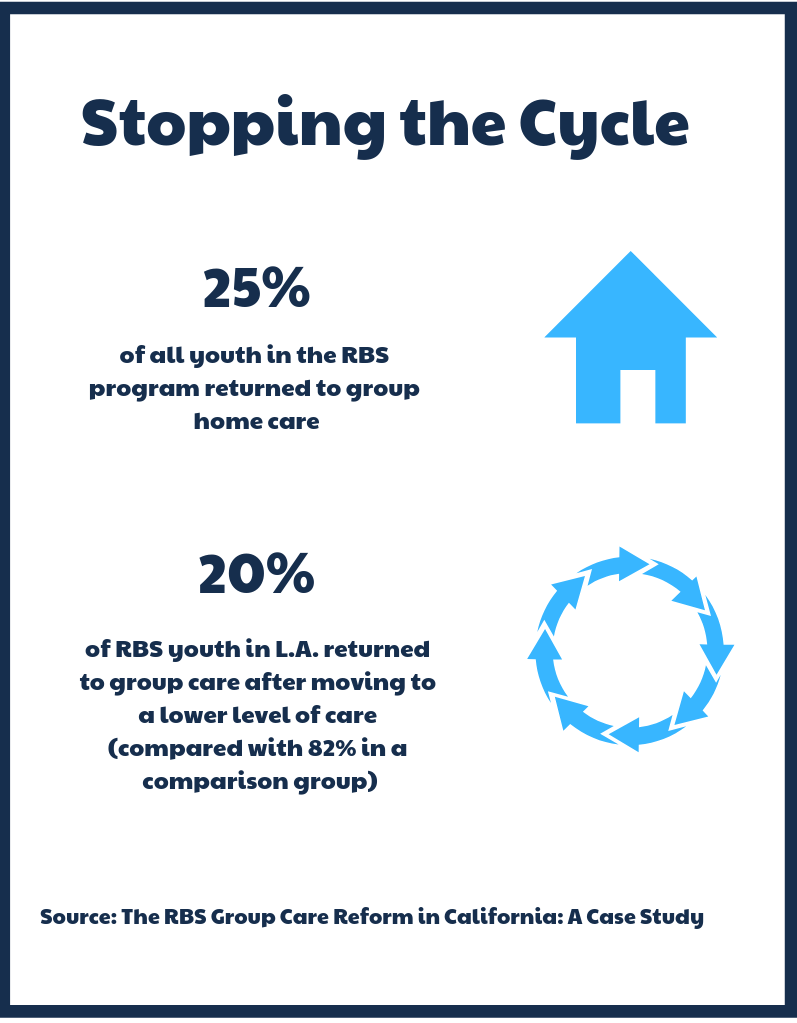

The seeds of this experiment were sown years earlier with an influential pilot project that took place in four counties across the state, starting in 2010. The Residentially Based Services (RBS) project provided an impressive proof of concept: it was possible to send youth back to family settings after a brief intervention without the child boomeranging back into the system’s deep end. The calcified culture of group homes — institutions that have long served as poor parents for foster children — could change.

Though the RBS experiment finally wrapped up at the end of 2018, its influence lives on in both California’s Continuum of Care Reform and federal group home reform. But there are many remaining questions about whether the project’s successes will become a reality for the vulnerable youth caught up in California’s foster care system.

“This is the chance of a lifetime to overhaul the system,” said Khush Cooper, a researcher and consultant who worked as a local implementation coordinator for the RBS project in Los Angeles County. “It is possible. We saw it happen with RBS. It is possible to send really challenged kids home quickly and to keep them there. We don’t want to have implementation issues fritter this chance away.”

A Long History of Group Homes

Group homes have been a key part of the legacy of child welfare in the country. Many of the largest and most established group homes today trace their origins as orphanages back to the 19th century. From the start, these religious and philanthropic organizations served many children who already had parents, but who were seen as providing inadequate care for their offspring. At the start of the 20th century, nearly 125,000 children were living in institutions across the country.

Even as many of these legacy orphanages began to work with youth in foster care who had high levels of mental health and behavioral challenges, the result was often the same: a sizable chunk of youth spent long periods of time in a placement of last resort.

In recent years, much greater attention has been paid to exactly which children are ending up in congregate care. According to the most recent federal foster care census, a total of 13 percent of all children placed into foster care are living in either a group home (6 percent) or another institutional placement like a shelter (7 percent).

In 2015, new research released by the federal Children’s Bureau connected the dots for the first time. About 41 percent of a national cohort of youth living in congregate care placements had no clinical reason for being sent to live in an institution Thirty-one percent of foster children across the country living in congregate care were 12 and younger.

Part of the issue is that youth who end up in group homes or residential treatment centers are among the most vulnerable youth in terms of mental health. But poor lifelong outcomes are also a function of the institutional nature of care, which can never replace the nurturing dynamics of a healthy family.

“We’re not going to be walking them down the aisle,” said RBS consultant Cooper, who also worked at a group home earlier in her career. “We’re not going to be taking them to the airport or dentist appointments when they’re adults. We’re not their family.”

Promising Returns

In 2006, 11.5 percent of California’s children in foster care were living in group care. But California was spending almost 50 percent of its foster care funding to support them.

The Residentially Based Services (RBS) pilot emerged as a means to re-imagine a different way of providing care to children in these facilities. According to the authors of an early concept paper, group homes would now become a train instead of a station, an intervention rather than a place to age out of the system.

Starting in 2010, four participating counties – San Bernardino, Sacramento, Los Angeles and San Francisco – began placing children into the pilot project, including 52 beds among three providers in Los Angeles.

Under RBS, children received one plan of care, supported by a child-and-family team that helped make decisions. That plan had several defining characteristics: a coordinated care team to follow a child from residential into community placements; ongoing crisis stabilization resources for the family receiving a child; family search and engagement support that started the first day a child entered group care; and six months of aftercare for the child and family.

In 2014, an evaluation funded by Casey Family Programs revealed the results of the RBS project. Youth who participated averaged one fewer placement than other youth, and in L.A., only 20 percent returned to group care after their experience, compared with more than 80 percent of a control group.

In 2014, an evaluation funded by Casey Family Programs revealed the results of the RBS project. Youth who participated averaged one fewer placement than other youth, and in L.A., only 20 percent returned to group care after their experience, compared with more than 80 percent of a control group.

The results of RBS were particularly strong in Los Angeles, where the gains were far and away the highest. There, RBS youth were able to move out of a group home and into a family home in a little more than eight months, compared to 20 months for a comparison group that did not participate in the project.

That success came with substantial financial returns. In the first four years of the project, L.A. County’s child welfare agency and three providers netted $7.4 million in savings, to be split between them.

A New Business Model

Joe Ford, a manager of residential programs at Hathaway Sycamores, has spent nearly 25 years working with youth in group homes, starting with overnight shifts early in his career. To him, the RBS model has meant a paradigm shift even in the way he talks when he’s around young people living on the grounds of the residential treatment center in the hills above Los Angeles.

“I don’t like our kids to refer to [Hathaway Sycamores] as a placement. I don’t want them to ever call this home either because our job is to get them to their home,” Ford said. “We’re no longer in the business of raising kids.”

That’s one of the many small but significant changes created by RBS, according to conversations with group home providers and advocates. Where group home staff might have once had adversarial relationships with biological family members, under RBS, institutions now see themselves as partners with family.

At Hathaway Sycamores, that has meant saving a room on campus for family members of youth in care in the hopes of helping family members develop relationships with youth.

“We’re not out here trying to save these kids from parents,” Ford said. “We’re including the families in the process and really involving them in the treatment process.”

But the transition to a new way of working with children and families has not been without its difficulties. Chanel Boutakidis, CEO of RBS provider Five Acres, said that staff turnover was at one point twice as high for the RBS program than Five Acres’ more traditional congregate care services.

Under RBS, staff had to do more than just make sure children are being taken care of. Now they must also work intensively with family members and prepare young people to live in the community. It took almost two years for Five Acres to put into a place the new culture, Boutakidis said.

“This is not something that residential treatment staff in any agency in California have really wrapped their minds around,” she said. “When we went to RBS, [staff] were used to being healthcare workers, making sure that children woke up in the morning, brushed their teeth and did their morning routines, had a healthy breakfast, went to school, and helped with their homework, which is very parental. Now on top of that, we’re also asking them to engage with families, help with visitation, and get them out of here as soon as possible. That can be really, really stressful. It is much more intense.”

Perhaps the most critical legacy of RBS was aftercare, a suite of support services designed to help children once they left group homes. Under the pilot, congregate care providers were required to continue serving children for up to six months after they landed in the home of a family member or with a foster family.

“You can’t get this type of child, who used to be in group homes for three years, get them out in six to nine months and expect that there isn’t going to be some drama when they transition into the community,” said Cooper, a UCLA researcher and RBS consultant.

“You can’t get this type of child, who used to be in group homes for three years, get them out in six to nine months and expect that there isn’t going to be some drama when they transition into the community,” said Cooper, a UCLA researcher and RBS consultant.

According to Janis Reid, senior clinical director at Hillsides, one of the three RBS sites in L.A. County, the team that follows children out into the community after they leave the group home is ready to step in at a moment’s notice and address obstacles that may sink home-based placements.

She tells the story of Mary,* a 15-year-old who was placed in the home of her cousin after a stay at Hillsides. Within two months of moving into the home of her cousin’s family, Mary had several meltdowns, including altercations with her cousin’s 14-year-old daughter that included physical fighting, hair pulling and spitting.

That could have easily led Mary’s cousin to give up on the arrangement. But the coordinated care team – which included a therapist, a child family specialist, a parent partner and facilitator – helped broker peace and negotiate boundaries.

Hillsides also offered up another key resource under RBS: crisis beds. When a youth was having a particularly difficult time and needed to return to campus to get back on track, RBS providers kept a bed open for this type of temporary arrangement, also known as respite care. The youth could return to a familiar place and get round-the-clock therapeutic help for their behaviors. Each RBS provider was required to keep one bed open at all times, something that the county paid for.

Last summer, Mary was able to stay at Hillsides for four days after her meltdown. When she returned to her cousin’s home, everyone was ready to start over.

“Because her family had that option, they didn’t feel backed into the corner,” Reid said. “Respite allows for calmer heads to prevail.”

But the menu of options available under RBS — including a robust aftercare program, family finding and crisis stabilization beds — are missing from the state’s congregate care model under its Continuum of Care Reform. With that reform effort, existing group homes must now transition to become short-term residential therapeutic program (STRTP), a clinically driven set of standards for residential care that owes much to the RBS vision.

“What could happen is that we lose the length-of-stay savings because folks are just not comfortable letting the kid transition out into the community, knowing that the blow-up’s going to come and the support’s not there,” Cooper said.

Moving Forward

There are signs that California’s progress on congregate care reform may be eroding. According to budget estimates from California, the state seems to be dialing back its expectations for transitioning more kids out of institutions and into foster homes.

There are signs that California’s progress on congregate care reform may be eroding. According to budget estimates from California, the state seems to be dialing back its expectations for transitioning more kids out of institutions and into foster homes.

According to a 2017 budget estimate, California projected that approximately 65 percent of foster youth living in group homes would transition to a foster family home or relative placement, and 20 percent would transition to STRTP placements under its child welfare reforms. The rest would be placed in an intensive foster home.

By January of 2018, the estimates had changed considerably. The state was banking on only 35 percent of these youth transitioning to a family home, with 45 percent headed to residential care. New California Gov. Gavin Newsom (D) continued a massive new investment into the state’s Continuum of Care effort this year, but his budget estimates also forecast that even fewer foster youth will transition into home-based foster care from group homes than had previously been projected.

“It’s like cutting the RBS vision in half,” said Boutakidis of Five Acres. “We’re going to do the residential portion but we’re really not going to do the community portion and that’s the part that you’re trying to get to stick. It’s going to take another year and a half, two years to get that child to permanency now.”

“I think we’re working on the margins at this point. I don’t think we’re going to see any wholesale declines, I doubt we’re going to see it cut in half again,” said Carroll Schroeder, the recently departed executive director of the California Alliance of Child and Family Services, which represents most of the state’s group home providers.

Facing Adulthood on His Own

“Am I doing it right?” shouts Jacob McCleary’s roommate, booming out of their apartment.

While his roommate cooks, McCleary sits outside the two-bedroom guesthouse located on a sleepy residential street in Alhambra, part of a group of apartments set aside for young people who have just emancipated out of the foster care system. The apartment has few amenities or furniture, but it’s the first place he can call his own since leaving the last group home, Hathaway-Sycamores, on November 16.

“Is it burning?” McCleary asks.

“I don’t know,” his roommate hollers. “You better come over here.”

Before he entered the county’s foster care system, McCleary cooked for himself at his aunt and uncle’s home. In the small kitchen of his new transitional apartment, McCleary helps his roommate avoid another culinary mishap. His roommate’s last dinner had been scorched on the stove, setting off the smoke alarm and flooding their apartment with smoke.

Soon after he turned 18 in August, McCleary decided to leave foster care, wanting no more figurative or literal bonds to county care, where he says he had to deal with hospitalizations, assaults and the arbitrary confiscation of his property by staff and social workers.

McCleary is relishing new possibilities outside the strict schedules of institutional life, but he also manages regular anxiety in mastering new routines and experiences like keeping a budget for weekly trips to the store. This month, McCleary is starting classes at a local community college, the first time he’s been able to have a say in determining the next step in his life.

As a fledgling mental health advocate, McCleary is beginning to put his recent experiences of foster care into perspective.

“Sometimes pulling kids out of their homes and putting them into placements is a lot worse than actually just staying in those homes,” McCleary said. “When you’re living in a group home, it’s easier to get the basic things you need in life. But it’s harder because you’ve never actually had the experience of getting stuff yourself; people have always been handing it to you.”

This story was produced by The Imprint. It was supported by the Fund for Investigative Journalism and was produced as part of “Reporting Vulnerable Children in Care” program, a journalism skills development program run by the Thomson Reuters Foundation, in partnership with UBS’s Optimus Foundation.