In a rare juvenile hall visit, a reporter observes hopes and dreams inside a college classroom.

Bars were the backdrop for this California college classroom, where eight young men engaged in deep discussion last month about the nuances of anxiety. Psychologist Shani Robins, who teaches at Stanford University, Foothill College and Santa Clara University, instructed the course.

Robins’ animated face appeared in a life-size projection on a classroom whiteboard, broadcasting his considerable charisma. The students focused intently, their eyes locked on the professor throughout the half-hour class, possibly due to a lack of distractions. In this classroom, there are no iPhones, backpacks or the opportunity for side talk.

Clad in purple T-shirts that read “San Mateo County Youth Services Center,” Robins’ students were all locked up in juvenile hall.

Robins’ psychology class will earn participants 10 high school credits plus three college credits. It is one of several dual-enrollment courses offered through Project Change, a program based at the College of San Mateo. A reporter from The Imprint was granted access on the condition that the names of students would be kept confidential.

Project Change works with young people during and beyond their incarceration. Those who leave detention settings and enroll at the college located on 153 acres with panoramic views of the San Francisco Bay receive free books and tuition, priority enrollment, and a network of staff and volunteer mentors.

More young people in California now have a similar opportunity. The state has dedicated $15 million to community college programs for detained youth, including dual enrollment programs modeled on Project Change.

“It is a huge, historic move for California,” said Katie Bliss, California higher education coordinator at the San Francisco-based Youth Law Center. Bliss spent time in the San Mateo County juvenile hall as a teenager, then went on to launch Project Change in 2015 while teaching English at the College of San Mateo. The college has been a local institution since 1922, and now serves 13,000 students a year.

“There isn’t any other state in our country that has invested this kind of funding in higher education for this population,” Bliss said.

Project Change Program Manager Nick Jasso was also incarcerated as a teen. He too went on to attend the College of San Mateo, then graduated from the University of California, Los Angeles, with the support of Project Change.

Jasso said he is looking forward to seeing more students receive similar opportunities as the program expands statewide.

“It was this constant undying belief in me and all the other students that made me want to push and push and push,” he said. “The things that happened to us don’t have to happen to other people.”

New opportunities for a changing population

The expansion of college courses inside juvenile halls comes at a crucial moment for California. On June 30, the state Department of Juvenile Justice — which houses young people adjudicated for serious offenses — will close down for good, leaving county detention centers with the challenge of housing and educating more young people until they turn 25.

One current 18-year-old college student entered the San Mateo County Youth Services Center shortly after the state halted new admissions to its youth prisons in June of 2021. He expects to remain at the facility for seven more years.

The teenager graduated from high school a few months ago and jumped right into the college curriculum, taking classes in communications, business and kinesiology — a field of study the aspiring personal trainer hadn’t known about until he joined Project Change.

“Growing up, I wasn’t really into school,” he said in an interview, sitting at a table in the facility’s well-stocked library. “I’d just go to socialize, mess around and talk to the kids. Now, I understand that education is way more important. Now I take it seriously.”

The teen described his current goal as completing his associate’s degree and then transferring to a four-year university, possibly Cal Poly San Luis Obispo, which he once visited once while living in a nearby group home.

“There isn’t any other state in our country that has invested this kind of funding in higher education for this population.”

— Katie Bliss, Youth Law CeNTER

The Youth Law Center’s Bliss said seeding this kind of ambition is central to Project Change.

“There is so much stigma and negative perceptions about what our youth are capable of and who is ‘college material,’” she said. Offering college courses to detained youth “sends a message to them about who they are and what they can become.”

Building a statewide model

On the March 23 afternoon The Imprint visited San Mateo County’s juvenile hall classroom and library, the atmosphere was peaceful. The wing dedicated to classrooms overlooked a green field circled by a running track. Chickens rooted quietly in a coop in a corner of the yard.

Inside the classroom, curiosity was on full display.

“I have a question, Shani,” asked one student whose hand remained raised for most of the psychology class period. “Was teaching hard at the beginning? Was there social anxiety?”

“A little bit,” Robins said in a Socratic turn, “but remember, when you feel anxiety, it is …”

“An opportunity to practice!” multiple students responded in unison.

Soon, Robins was fielding a barrage of existential questions: “What if someone’s whole life is a delusion, but they don’t realize it and they’re genuinely enjoying it?” That gave the conversation the feel of a late-night dorm room colloquy, not a group discussion taking place amid cinder block walls under the watchful eye of uniformed guards. The students engaged their professor in a wide-ranging discussion that touched on Seinfeld, stage fright and the properties of gravity.

California’s $15 million dollar investment in settings like these has the potential to offer this kind of experience to justice system-involved youth across California. The funding will be disbursed through the Rising Scholars Network, a consortium of community colleges creating academic opportunity for students who have experienced the juvenile and criminal justice systems.

Gina Browne, dean of educational services and support at California Community Colleges, noted that educational opportunities reduce recidivism, thus serving personal and public safety goals.

“We know that students are not going to be in a juvenile facility forever,” Browne said. “We want to make sure that they are prepared.”

“If these kids are offered the opportunity, a lot of them will run with it. Without this, no one is ever going to tell these kids that they’re worthy enough.”

—Jacqueline Rodriguez, former Project Change participant

As the statewide expansion rolls out, courses will be offered on campuses and in juvenile detention facilities, with additional support for formerly incarcerated students that includes ongoing college tuition, food, housing and transportation.

Hailly Korman, a senior associate partner at Bellwether, a national nonprofit focused on improving education, praised the model.

“I don’t know of any other state making this kind of community college-based investment in this work,” she said.

Post-secondary education in youth settings is likely to become more important nationwide, Korman added, because of new state laws that keep some adolescents in youth facilities into their 20s, rather than transferring them to adult prisons.

She added that while college programs are valuable, in order for them to succeed, secondary education inside juvenile detention facilities needs to improve as well.

“There are still quite a lot of young people who don’t even earn that high school credential,” Korman said. “I can’t enroll in community college if I can’t read.”

Education in youth detention facilities tends to be fractured and inconsistent, agreed David Domenici, executive director of BreakFree Education, a nonprofit that advocates for quality education in juvenile facilities. Students may miss out on school when understaffed facilities have no one available to move them from housing units to classrooms and back again. Further hindering their education, teachers are often asked to work with students of different ages and abilities at the same time.

That was the experience of Jacqueline Rodriguez, a former Project Change participant. When she was incarcerated at 12 at the San Mateo County juvenile hall, she said she was the only girl her age in the facility. So while teachers focused on delivering high school-level material, she was doing workbook packets in the back of the class.

“I felt like my education was being robbed from me,” she said. “I got great grades in there, but I got out knowing literally nothing.”

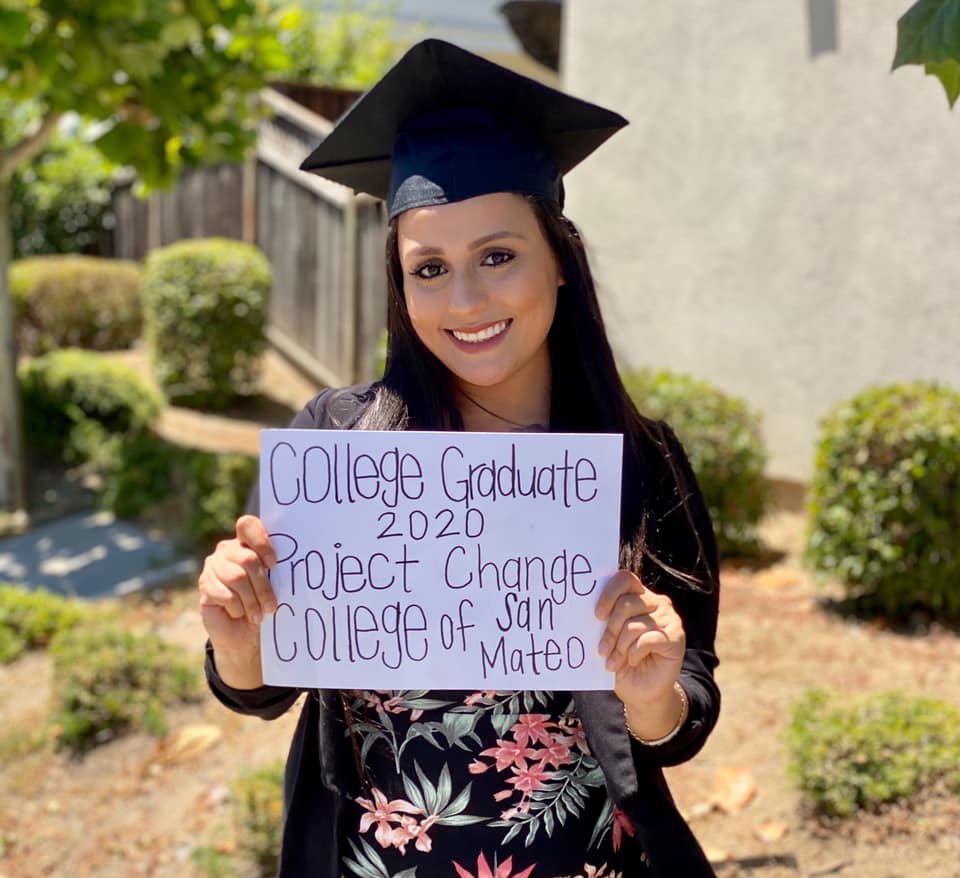

Several years after her release, Rodriguez connected with Project Change. With that support, she enrolled in community college, then transferred to the University of California at Los Angeles. She graduated with honors and now works with Bliss as as an advocate for the Pathways to Higher Education Project, while she waits to hear back from law schools.

“If these kids are offered the opportunity, a lot of them will run with it,” Rodriguez said. “Without this, no one is ever going to tell these kids that they’re worthy enough.”

A glimpse of the future

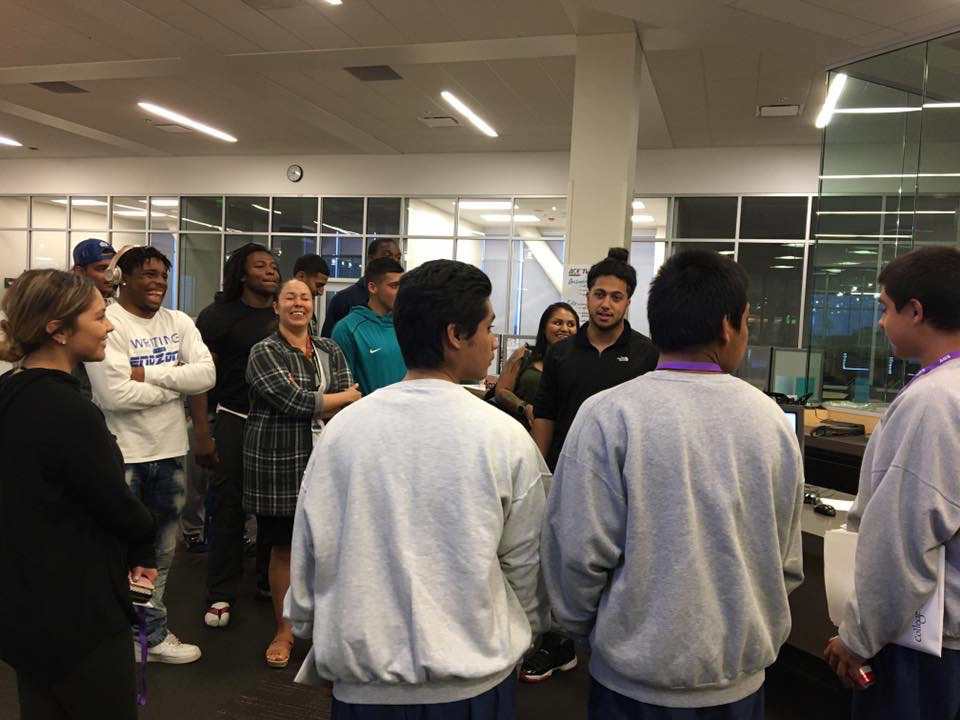

Inside the Youth Services Center last month, Jasso took over the second half of the class by introducing three guest speakers who had come to the detention center to celebrate the midterm mark of the semester.

The San Mateo County facility tucked on a Peninsula hillside has a capacity of 180, but due to dramatic declines in youth crime and incarceration, held just 26 youth in February.

This day was special. Over wings and cheese fries brought in for the occasion, all three speakers described winding educational journeys that began behind bars, took off with help from Project Change, and ended at places like San Francisco State University and UCLA.

“Ten years ago, you would have been talking to a whole different person,” said Patrick Tupoumalohi, describing his former self as a high school dropout who “didn’t really see a future.”

Today he is finishing up the second of two associates’ degrees at San Mateo College. Next, he plans to transfer to San Francisco State University, where another program, Project Rebound, offers support to formerly incarcerated students.

“Getting into higher education, you start thinking differently, talking differently, seeing things differently,” he told the younger students. “Once you’re in school, that creates a support system behind your back and you start wanting more for yourself.”

His goal moving forward, he told them, is to “weigh out my priors with more degrees.”

As the class period wrapped up, young people rushed to box up leftover wings.

“C’mon, we gotta go!” shouted a Youth Services Center staff member. The young men organized themselves into a straight line to exit the classroom.

“Wherever you may go, let this be the beginning,” Bliss told them before they headed out to housing units, which consist of two tiers of cells surrounding a day room. “I was in this juvenile hall 20 years ago. Back then, you had to fight just to get your high school diploma. It’s powerful to see that turning around. All of you are just starting on your paths.”