Latino families come to this country for a new life, but two generations later, many are struggling and their children increasingly end up in foster care.

By Daniel Heimpel

Credit: Eytan Elterman

Social worker Elba Covorrubias and an LAPD officer investigate an allegation of child abuse.

It is a cool winter night as Elba Covarrubias, a 30-year-veteran of Los Angeles County’s Department of Children and Family Services (DCFS), cuts the dark of poor, suburban and largely Latino Pacoima with the bright beams of her big blue 1987 Mercury Marquis station wagon. Endless rows of single-story homes, most with bars on the windows and doors, flit past through the car window.

“We have an 18-year-old female who has been allegedly impregnated by her stepfather,” she says clinically. “At risk is also the 10-year-old sibling who also resides in the home. Allegedly the mother is aware of the consensual relationship between the daughter and stepfather and has allowed the stepfather to continue to reside in the home.”

What Covarrubias will find is a family in crisis and an 18-year-old girl hiding her fast swelling belly under her big, black puff coat. When that baby is born, he will come into the world with a host of the risk factors that researchers are tying to heightened rates of child maltreatment. Among these risk factors are being born to a young mother, who was victimized as a child herself and who will soon find herself socially isolated.

Beyond these intuitive even obvious risks, new research suggests something much more insidious: that this baby will have a heightened probability of experiencing maltreatment and abuse because he is third generation Latino.

In the United States of America, immigrant Latino families are being torn asunder, and research shows that the strengths they bring to this country are quickly lost to powerful and often damaging acculturation.

“Despite cross generational gains in economic integration, there are negative consequences to integration,” University of Illinois at Chicago researcher Alan Dettlaff wrote in a 2009 study on the subject. “Drug abuse, bad parenting skills, recent history of arrest and high family stress, all those things are more likely in U.S.-born Latino families than foreign born families.”

For decades, child welfare researchers, foster care administrators and lawmakers vexed over what some believe is an over-inclusion of African-American and Native American children in foster care, as compared to white children. All the while, Latino children have been catching up, entering the system at ever-higher numbers and concentrations with little or no attention.

Credit: Eytan Elterman

Covarrubias checks for signs of physical abuse with a flashlight in a home in North Hollywood, CA.

A handful of child welfare researchers are starting to shine light onto a problem overwhelming in its immensity, daunting in its complication and foundational to the future of foster care, maybe the country.

In 2010 the number of Latinos in the U.S. exceed 52 million, or 17 percent of the total population. Nearly one quarter of the 74 million children in America were of Latino decent. One in four babies born in America today is Latino.

Now, compound these swelling numbers of Latino children with the emerging research about the degradation of family strengths in second and third generations. What you have is a reasonable expectation that more Latino children will suffer the type of severe abuse and neglect that lands them in the foster care system and that overall numbers of children in foster care will also rise.

In 2000, almost half of California’s population was Latino, while one third of its foster care population was comprised of Latino children. By 2010, half the state’s population was Latino, roughly on par with the percentage of Latinos in the foster care population. In a decade an underrepresentation of Hispanic children in California’s vast foster care system had become parity.

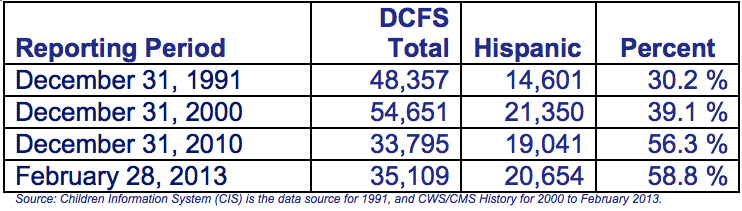

On the last day of 1991 there were nearly 50,000 children under DCFS supervision in Los Angeles County, 14,000 (30 percent) of whom were Latino. On the last day of February 2013, the total number of children had dropped to 35,000. The number of Latinos had shot up to more than 20,000, accounting for almost 60 percent of all children involved in the county’s foster care system.

The increased overall numbers is a trend that holds true across the country. While the number of Latino children doubled over the past 15-20 years, so did the percentage of those with confirmed cases of child maltreatment.

In 1995, 10 percent of Latino children had substantiated cases of abuse and neglect; by 2010, that share had jumped to 21.4 percent, according to national data analyzed by Dettlaff.

“Similarly, the population of Latino children in foster care has more than doubled from 8 percent in 1990 to 21 percent in 2010,” he added in an email to The Imprint.

But understanding why this is happening requires a deeper look at how “Latinos” are categorized. Ruben Rumbaut, a Professor of Sociology at the University of California Irvine, who has devoted much of his career to studying Latino population growth in the United States, says that this is an issue that will require much more than research based on amorphous groupings by ethnicity of race.

“As I like to tell my students,” he quips, “race is a pigment of our imagination.”

And when one focuses on generations the existing and emerging research points in a startling direction.

“The increase of Latino children in the child welfare system is likely due in part to a growing population of third generation Latino children, who are at greater risk of child welfare involvement than their first and second generation counterparts,” Dettlaff says. The longer your family lives in the United States: the more your children are exposed to child maltreatment.

A major study released this year supports Dettlaff’s premise, and suggests a steady increase in foster care removals among Latinos. The study, led by USC’s Emily Putnam-Hornstein and Barbara Needell of UC Berkeley, linked birth records for all 550,000 babies born in California in 2002 to Child Protective Services data through each child’s fifth birthday. The researchers were able to separate out babies born to mothers who were Latino immigrants from those who were born to Latino mothers also born in the United States.

Third generation babies born to U.S. born Latino mothers were twice as likely to be referred for child maltreatment than those born to foreign born mothers; almost three times as likely to have a case of substantiated abuse; and more than four times more likely to enter foster care.

This generational loss of protective factors and increased risk appears consistent in other states. A report released by the Urban Institute in 2007 provides an emphatic illustration of what is happening in terms of entrance into foster care.

Latino immigrant children, most of them Mexican, made up one percent of Texas’ foster care population, but seven percent of the total population. The children of immigrants (second generation) represented eight percent of the foster care population and accounted for 20 percent of the total child population in Texas. Latino children born to Americans represented 33 percent of the foster care population while representing only 22 percent of Texas’ overall child population. By the third generation Latino children had gone from marked underrepresentation to steep overrepresentation.

“As a culture, we tend to be so nationalistic,” Dettlaff says “We think acculturating to the United States is a really positive thing. But it is really not.”

Or as Rumbaut puts it: “Americanization is hazardous for your health.”

At the Foothill Police Station in Pacoima, Covarrubias has just finished an interview with the man suspected of impregnating his wife Celia’s 18-year-old daughter Caroline: the man’s step-daughter. [Names of everyone but Covarrubias have been changed to protect the identities of minors] Like Celia, Rogelio was born in Mexico and speaks very little English. This is in stark contrast to Caroline and 10-year-old Mariela who are both American-born and fluent.

On this brisk night, the police had come out to the family’s apartment after calls of domestic violence. It was the second time the police had been called in similar circumstances, the first time Celia claimed her husband had tried to gauge her eyes out.

Covarrubias walks out of the interview room and into the Spartan police station reception area where a television drones over the hushed conversation going on between Caroline and her aunt Angela. Celia and 10-year-old Mariela loiter outside in the cold; Celia incapable of looking at Caroline because of the rift caused by the unseemly love affair.

“How long have you had a relationship with him?” Covarrubias asks Caroline.

“We just started like when I turned 18,” Caroline answers, her voice barely audible. She has an oversized puff coat on and looks worn and sad. Angela, seated next to her, can do little else than shake her head at the scene unfolding before her.

“But your mom found you in ‘07. There was a report.”

“In ‘07 that was the report I made about the guy in school,” Caroline says.

“No that was ’06… The report in ‘07 was when your mom came home and found you and Rogelio in the bedroom.”

“I never heard about that,” Caroline says.

“No but somebody did, because they knew the story. So, I suspect that it has been going on for a while and Rogelio…”

Covarrubias pauses and nods her head while pursing her lips, “he was very truthful.”

“So what do you want me to tell you?” Caroline asks. “Because from my understandings they [Eva and Rogelio] were gonna get divorced. They were already filling out the papers and she was gonna move out. And we were gonna move out.”

“You and Rogelio?” Covarrubias asks, incredulous that this young girl is planning to start a family with her mother’s husband.

“Yeah he’s gonna help me with school until I can get a small career and we will see after that.”

“Mija that is so wrong on so many levels,” Covarrubias says. She and Caroline’s eyes are locked, “So wrong,” she says.

Credit: Eytan Elterman

Jennifer Lopez, former Director at Command Post, stoops over a Latino baby boy. Just hours earlier his brother had been killed by the baby’s parents.

But as wrong as it is, this is the reality that Covarrubias has known for three decades, most of that time spent at Los Angeles County Department of Children and Family Services’ (DCFS) “Command Post” where in 2012 an average of five children were removed each night, 150 a month, 1,800 a year.

“Think about the immigrants,” she says. “Think about the neighborhoods where they have to live in.”

Often, Covarrubias explains, poor immigrants start their American dream in downtown L.A.’s Skid Row only to “move up” to increasingly Latino South Los Angeles, formerly known as South Central. Along the major corridors – Figueroa, Vermont, Crenshaw – gangs run the streets, she ads, and recruitment is often straight coercion.

“It’s scary. I hear kids who say they have no choice. In some areas you have to just do what you are told.”

This is not surprising when considering the portrait painted by Loyola Marymount University professor Cheryl Grills. Whether black, white or Latino, Los Angeles’ poorest enclaves are breeding grounds for broken families, violence and drug abuse.

Grills regularly visits with county officials and community-based organizations with series of slides mapping South Los Angeles. “When I show people this stuff there is literally gasping in the room,” she says.

Credit: Cheryl Grills

Prevalence of Liquor stores in South Los Angeles, where many Latino families live.

One slide is lit up with countless red stars indicating the concentration of liquor stores up and down the broad avenues of poor Los Angeles. “There are literally more liquor stores in South Central than the whole state of Rhode Island.”

When she gets to a map that shows the level of parolees and probationers in need of mental health services compared to the dearth of mental service providers, her word is simply “absurd.” But more than absurd, what she and her slides describe is something insidious and ultimately dangerous.

In regards to the evidence that second and third generation Latino children enter foster care at higher and higher rates, Grills is unsurprised.

“Being newly arrived, they haven’t yet been infected by the neighborhood,” she says. “The neighborhood will infect you emotionally, mentally and medically. It is harmful to your health to be a person of color in America.”

Jerrell Griffin is the assistant regional director of DCFS’ Wateridge office, which covers those gang-infested, poverty-stricken zip codes where so many Latino families settle. Griffin left a job teaching at an L.A. high school for DCFS, and now oversees one of the most overburdened offices in the 7,300-employee department. In 2012 Wateridge had 5,555 reports of child maltreatments, and an average caseload of 37 children per worker.

“The school systems are failing, the health care system is failing, the trauma centers are closed,” he says.

“The conversation needs to elevate much higher up,” he adds. “It’s like we are trying to get rid of the termites in a house when they have eaten up the whole foundation. We need to get our priorities together as a nation, we do not recognize children as our assets and this what we end up with.”

Despite economic gains and often higher levels of education in second and third generations, Dettlaff writes in a 2009 paper that, “there are there are negative consequences to integration including family disintegration, lack of family stability, and declining child health outcomes in second generation immigrant families.”

A study by Michelle Johnson-Motoyama of the University of Kansas, Dettlaff and USC’s Megan Finno, published in 2012, used the data from the 2nd National Survey of Child Welfare and Adolescent Well-Being to analyze at the differences in child victimization rates between the children of American and foreign-born parents.

Immigrants were more likely to be married, while American parents were more frequently described by social workers as unable to meet their “family’s basic needs,” actively engaged in substance abuse, “and to have a recent history of arrest.”

More involvement with the justice system may augment a projected increase in Latino foster. According to research Rumbaut published in 2008, one of the consequences of this generational “shift” is that the incarceration rates among Latinos start resembling those of African Americans.

Only one percent of the immigrant population is incarcerated compared to 6.7 percent of U.S. born Latino men, according to Rumbaut’s research. That is well below the 11.6 percent incarceration rate literally decimating the black male community, but an indication of what could be on the horizon.

This permeates the maintenance of two-family homes, the lack of which is a strong indicator of involvement with the child welfare system. A 2011 study out of UC Berkeley conducted by researchers Emily Putnam-Hornstein and Barbara Needell found that no paternity had been reported in the birth records of 7.1 percent of children born in California in 2002. Almost a quarter of children born that year and subsequently reported for maltreatment by age five had no paternity reported in their birth records.

That the Latino population is growing in this country is incontrovertible. Not only is the Latino population in the foster care system growing along with it, but a historic underrepresentation is ballooning into disproportionality. As the number of U.S.-born Latino parents continues to increase, research projections suggest that far more Latino youth will enter foster care unless risk factors associated with those parents change.

As the tide of Latino children entering the foster care system rises it will be left to the foster care system to clean up an American mess much broader and deeper than their limited resources can solve.

Caroline, now 20, is still in Los Angeles, somewhere in the San Fernando Valley, living with a baby boy and the baby’s father, Rogelio. I called her one morning last year, before her cell phone number changed and Covarrubias and I lost track of her.

“I’ve moved on with my life,” she said, her voice groggy in the late morning. “My plans are to finish school and maybe have a part time job and keep studying until I finish so I can have a career.”

She didn’t know where her mother or sister were living.

“It is hard with the baby,” she added. “It feels lonely. But I am getting used to it, because I have my own little family now.”

The baby started to cry. She hung up the phone.

Daniel Heimpel is the founder of Fostering Media Connections and the publisher of The Imprint.