By Lauren Gonzalves

Since 2008, Washington State’s Passport for Foster Youth Promise Program has helped hundreds of foster youth enroll and stay in college.

The program was launched in 2007 to increase the number of foster youth participating and succeeding in postsecondary education. According to a 2011 legislative report, “the program is a response to findings that foster youth are less likely to secure the benefits of higher education than either the population as a whole or other disadvantaged groups.”

The started as a six-year pilot and includes three primary components:

- A student scholarship awarded each academic year up to $4,500.

- Direct payments to participating colleges for each foster youth they enroll.

- A partnership with the College Success Foundation, an organization dedicated to supporting foster youth, to provide on-campus wraparound support to students, and training and technical assistance to campus staff.

Alexia Everett is the Senior Program Officer for Foster Youth College Access and Success for the Stuart Foundation.

Photo Credit: Linkedin.com

Alexia Everett, who is now the senior program officer for Foster Youth College Access and Success at the Stuart Foundation, worked alongside State Rep. Reuven Carlyle (D) to launch the program.

“The actual structure of the program was the brainchild of the Rep. Carlyle,” Everett said. “He himself had an alternative upbringing and just feels really passionate about education. When he talks about the story, he talks about how he was in a coffee shop one day and he actually wrote this down on a napkin.”

Everett says Passport is different from other states’ postsecondary programs for foster youth.

“Essentially [Carlyle] wanted to provide financial assistance for students to be able to choose their college and their career but he knew that wouldn’t be enough…he said we need to get colleges to care,” she explained.

Now, Passport provides a scholarship to eligible former foster youth (that goes beyond the Chafee Education Training Voucher) and pays colleges for every foster youth they enroll.

”That really adds up,” Everett said. “There are some schools that are receiving thousands of dollars.”

And, there are checks and balances on schools that receive additional funding to ensure that the money goes back to foster youth.

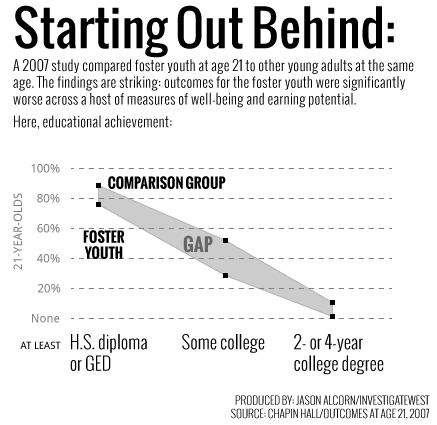

Foster youth are significantly less likely to attend a postsecondary institution than the general population.

Photo Credit: www.invw.org

“Each campus who says I want to receive dollars for foster youth has to agree to have a point person who understands the needs of the foster youth…and they have to be willing to be ensure that their financial aid packages [offered through Passport] are as robust as possible,” Everett assured.

Lastly, Everett explains that the final component of Passport also gives Washington State’s program an edge: “a third-party backbone of support” also known as the College Success Foundation.

The Foundation provides direct support to Passport students by monitoring academic progress, and helping to strengthen working relationships between community providers and colleges.

According to Everett, the multidimensional design of Passport is what makes it such a comprehensive, supportive program. Beyond the resources offered in the postsecondary years, Passport also maintains a secondary education component called Supplemental Education Transition Program (aka “SETuP”), which starts prepping teenage foster youth before they even leave for college.

As found in the most recent legislative report, “more than half of the 200 continuing

The Passport program has helped hundreds of foster youth enroll and stay in college.

Photo Credit: www.invw.org

students in 2010-11 have been enrolled for two or more years, about 41 percent of persisting students continued from the previous year, 37 percent have attended for two years, and the remaining 23 percent have attended all three years [original cohort from 2008-2009].”

The 2011 report shows that the number of former foster youth enrolling in the program continues to increase each year.

Another piece that sets Passport aside is that a foster youth can remain in the program until he or she is 27. That is four years longer than the Chafee ETV program.

“As far as I’m aware, Washington is the only state that has done this to this point. It’s really the only model like this. What were hoping to do, is see what pieces of the model are working and see what’s replicable in other places.”

Lauren Gonzalves is a graduate student at UC Berkeley’s School of Social Welfare. She wrote this story as part of Fostering Media Connections’ Journalism for Social Change program.