As evidence mounts that punitive discipline makes students more likely to go to prison than to college, school districts in greater Los Angeles, including Long Beach Unified and Lynwood Unified, are shifting away from suspending students or citing them for truancy. Instead, they’re making greater use of restorative justice programs, as is the juvenile division of the Orange County Superior Court.

While student advocates support the focus on restorative justice, which rehabilitates offenders through reconciliation with victims and the community, they point out that schools still need to make headway in how they discipline youth. Racial disparities persist in suspensions and some schools routinely remove students from class without formally suspending them, they say, making suspension rates appear lower than they actually are. Los Angeles Unified School District has faced similar accusations as it works to drive down suspensions.

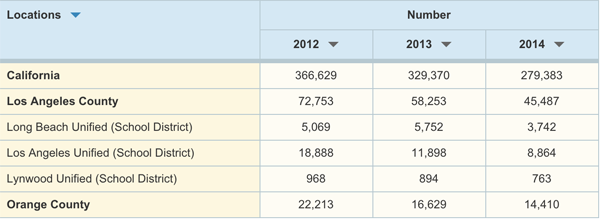

School districts throughout California are taking steps to reduce suspensions as well. Suspensions dropped statewide by 12.8 percent during the 2014-15 school year to 243,603 from 279,383 the previous school year. And they’ve fallen by 33.6 percent since the 2011-12 academic year, when 366,629 students were suspended.

“We’re finally noticing the pendulum swinging the other way to address really good programming for children and families,” said Orange County Superior Court Judge Maria Hernandez.

She presides over the juvenile court, where she overhauled the truancy program in 2012 because she objected to how it penalized youth and their families. That year, L.A. County also closed its 13 Informal Juvenile and Traffic Courts, which served truants. Officials said truancy citations weren’t a good use of the courts’ time. And LAUSD even introduced a truancy diversion program that led to the end of truancy sweeps and ticket task forces during the first 90 minutes of school.

Hernandez took issue with Orange County Superior Court’s truancy program because she felt “it wasn’t consistent with evidence-based approaches,” she said. “It was very punitive and not really serving its purpose.”

Many of the truant children came from dysfunctional homes, wracked by substance abuse, domestic violence and mental illness. Ordering such children out of class to attend court hearings and fining their families didn’t lower the number of truancy filings, but establishing a truancy response team with social workers, probation officers and others to meet the needs of families did.

Truancy filings in Orange County dropped from 256 in 2012 to 56 in 2015.

“If I can keep these kids out of the system, their outcomes are going to be a lot better,” Hernandez said. The judge sits on the steering committee of California Chief Justice Tani Cantil-Sakauye’s Keeping Kids in School and Out of Court Initiative (KKIS), which is working to reduce student absenteeism among a broad slate of goals.

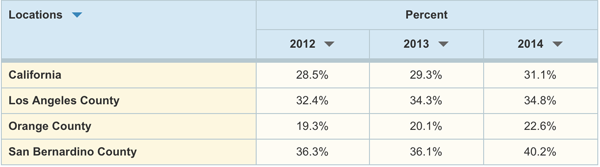

Percentage of K-12 public school students missing more than 30 minutes of instruction without an excuse three or more times during the school year. Data Source: California Dept. of Education, DataQuest (Jul. 2015). Credit: Kidsdata.org

Why Truancy Rates Are Rising Statewide

While truancy filings have dropped in courts statewide, the school truancy rate actually rose slightly—from 29.28 percent during the 2012-13 school year, with 1,902,509 truant students, to 31.14 percent during the 2013-14 school year, with 1,995,055. Students who have missed more than 30 minutes of school three different times without an excuse are considered truant.

The California Attorney General’s Office posits that the uptick in the state truancy rate likely stems from schools improving how they monitor student attendance. It points to Long Beach Unified as a district that managed to lower its chronic absence rate, even as truancies rose.

LBUSD lowered its chronic absence rate from 26.18 percent in the 2013-14 school year to 9.6 percent the following year. The district of nearly 80,000 students credits the drop in chronic absences to parent outreach and to school officials scrutinizing district data to pinpoint the schools with the most absences.

“There were about 30 elementary schools with pretty poor attendance rates and high truancy rates,” said Erin Simon, director of LBUSD’s student support services division. “I spoke with the school staff and most importantly with the parents and the families about high chronic absence and chronic truancy.”

Simon discussed with families the consequences of truancy in kindergarten and first grade, including how it results in 83 percent of students being unable to read on grade level by third grade.

Long Beach Unified also expanded the reach of its School Attendance Review Board (SARB), a group made up of school officials and community members to curb absenteeism. The district was named a 2015 Model SARB district for its efforts to reduce school absences.

Racial Disparities in Suspensions

Long Beach Unified not only cut its chronic absence rate but also slashed its suspension rate from 4.4 percent during the 2013-14 school year, with 3,742 students suspended, to 3.5 percent the following year, with 2,939 students suspended.

Black students, however, are most likely to be suspended from Long Beach schools. They comprised 14 percent of LBUSD students during the 2014-15 school year but more than a third of students suspended. This pattern can be found both state and nationwide.

In California, African Americans make up 6 percent of public school students statewide but 16.4 percent of students suspended.

“One intervention is to actually have some training [in schools] on what implicit racial bias is,” said Angelica Salazar, a senior policy associate with the Children’s Defense Fund in California. “We need to address this racial disparity and invest in some kind of intervention that has a racial lens.”

But Salazar applauds LBUSD for lowering its number of willful defiance suspensions, long criticized as the most subjective form of suspension. Defiance suspensions can include behaviors such as “talking back” to teachers, profanity or not following instructions.

Percentage of public school students in grades 7, 9, and 11, and non-traditional students reporting the number of times they had skipped school or cut class in the past 12 months, by race/ethnicity. Data Source: California Department of Education, California Healthy Kids Survey and California Student Survey (WestEd). Credit: Kidsdata.org

“We’ve seen a lot of progress in the numbers,” Salazar said. “In 2012-13, there were 5,647 suspensions [in Long Beach] for willful defiance and the latest data shows there were less than 1,000 during the past school year.”

Why Students Continue to be Removed from Class

Christopher Covington, a community activist who has worked with the Every Student Matters campaign to reduce school suspensions in LBUSD, suggested the reported numbers of willful defiance suspensions may not fully reflect reality. Some Long Beach high schools don’t formally suspend students for willful defiance but regularly remove disruptive students from class, he said.

“It’s considered like a detention,” Covington said. “They’re not being suspended off campus, but if a student walks into class and is defiant, the teacher calls an aide, and they’re suspended for that period. The environment is similar to a confined waiting room. They either have to sit on the floor and stare at the desk or stare at a wall.”

When asked about informal suspensions in LBUSD, Simon said the district uses progressive discipline, whenever possible, to address inappropriate behavior.

“The district’s ultimate goal is to reduce the recurrence of the negative behavior by helping students learn from their mistakes,” she said. But in some cases, students are temporarily removed from class, so administrators or other school officials can step in to address their behavior, she said.

“Interventions have become an integral part of LBUSD’s efforts to foster positive behavior, promote progressive discipline practices and keep students in school,” Simon said.

Overall, LBUSD reports just 909 willful defiance suspensions for the 2014-15 school year, down from 1,379 the previous school year.

How Lynwood Is Reducing Suspensions and Truancy

Long Beach is hardly the only district in the greater Los Angeles area to cut such suspensions. The Antelope Valley Union High School District nearly halved its number of willful defiance suspensions—lowering such suspensions from 3,030 in the 2013-14 school year to 1,712 the following year. During the same timeframe, Lynwood Unified in South L.A. reduced its willful defiance suspensions from 543 to 183.

Number of suspensions of K-12 public school students.

Data Source: California Dept. of Education, DataQuest (Jul. 2015). Credit: Kidsdata.org

Lynwood Unified Superintendent Paul Gothold said that he simply doesn’t believe suspensions are effective discipline strategies.

“When a kid is suspended, that does nothing to change behavior,” he said. Rather than using suspension as the first line of defense for bad behavior, the district gives students chances to correct their behavior, Gothold said. Troubled students also receive mental health services, and school staffers receive cultural proficiency training to better grasp the challenges community members face.

The district also takes measures to reduce incidences of truancy. During the 2013-14 school year, the truancy rate was 13.22 percent, less than half of the state rate. Gothold said that home visits and truancy sweeps have been successful for the district.

“We just at random have police cars patrol the streets, and if a student gets picked up, they’re brought back to school,” he explained.

Like Judge Hernandez, however, Gothold doesn’t support penalizing truant students with fines and court hearings.

Instead, he said, “Let’s find out what the real issue is and develop a plan of support. That’s 100 times more effective.”

Nadra Nittle is a Los Angeles-based journalist. She has written for a number of media outlets, including the Los Angeles News Group, the Maynard Institute for Journalism Education and About.com.

This story is part of a series funded by The Stuart Foundation on behalf of the California Chief Justice’s Keeping Kids in School and Out of Court Initiative.