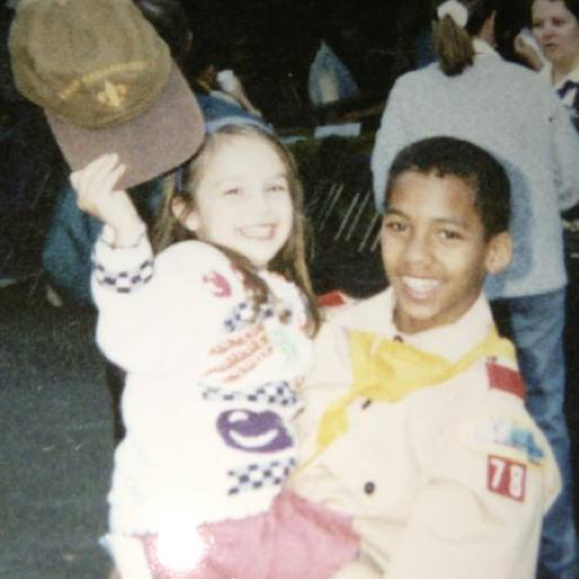

The author with her baby, Yuri. Photo courtesy of Katarina Sayally.

If you haven’t heard enough stories about what breaking the intergenerational cycle of foster care looks like, I want to share one. This is our story, and it’s a good one.

When I found out I was pregnant, the only fear I had was, “What if my baby ends up in foster care?” As a former foster youth who works in the field, I am constantly reminded of this possibility. One study found that mothers in foster care were twice as likely to have their children removed. In my master of social work program, I learned that the structured decision-making tool (that can determine whether a child welfare case is opened) assigns a point for risk if parents have been in foster care themselves.

I felt up against all of this and I wasn’t so sure I could overcome. But when my baby was born, the first thought that crossed my mind was “I love you.” Statistics cannot estimate the power of my love. They cannot limit the potential of my brilliant baby. They cannot write our ending before we have even begun. These are some of the values and practices I incorporate into my parenting to ensure that this baby gets to have the love-filled life all babies deserve.

Growing up, I heard people talk about me, and they often spoke around me. I was seldom engaged in conversation, only occasionally acknowledged. I was not given the opportunity to provide input or to process what was happening around me. And nobody ever really listened to me.

I talk to my baby constantly, sometimes responding with the sounds they make and regularly explaining what’s happening in their environment. This is all with the intention of developing their sense of security and autonomy. Maybe you have heard about this new fad of infant potty training. Well, it actually is an ancient indigenous practice and is less about potty training than it is about communication. For me this is about listening to my baby and showing them that they can depend on me to meet their needs. I am committed to honoring this baby’s voice, now and forever.

When a child enters foster care nobody is thinking about their financial future. I never got a piggy bank. So I opened my baby a bank account right away. I put the money that I would be spending on diapers in that account every month. I plan on giving them developmental opportunities to save, spend and manage their money throughout their life so that it’s not all new when they move away from home.

I don’t have a lot of pictures from my childhood, especially pictures with my siblings. The system took what should have been a family album and turned it into separate case files. I am still trying to find a way to bring our lives back together. In this picture, I am being held by my big brother and I have never seen a happier version of the two of us. Unfortunately, it’s one of my few memories of being held. Children need to be held.

Instead of physical touch, foster kids learn about liability and boundaries. Where I grew up, hugs were against the rules. Now I am almost always holding my baby. Not even just because I have learned about the importance of healthy attachment in my academic career. I hold my baby because it feels completely natural to love them. I have enjoyed learning about and using different baby carriers. My favorite is this ring sling because it is easy to bring everywhere. In the carrier baby can be close, hear my heartbeat, feel safe, and experience the world together with me (from washing dishes to grocery shopping, hikes and other adventures).

I spent a couple of days getting to know my baby before naming them. Ultimately I decided to create our own family name. I settled on Sayally (pronounced Sigh-L-E) to hold us together as we define what family can be. May my babies always speak truth to power (“Say all”) and live fiercely in their purpose (“y”=why). This also gave me the opportunity to pack a lot of intention into our new family. It doesn’t just have to be about breaking the cycle anymore.

Next time you hear about the dwindling odds of a good life for children of foster youth, I hope you remember our story of love and commitment. It is important to acknowledge and address generational cycles of abuse and neglect, but statistics cannot estimate the power of my love. My past does not determine our future. I know how to love this baby because I am capable of love even though the system never made me feel worthy. All the love the system took from my mother and grandmother, came back to us the day this baby was born.

Katarina Sayally is a 24-year-old mother and community organizer. She is an active member of the National Foster Care Youth and Alumni Policy Council and sits on the Advisory Board for Foster Youth Museum.