After lawsuit settlement, millions of dollars will be invested in providing more therapeutic settings, including specialized foster care and “hub homes.” Part one of a two-part series. Read part two here.

For years, hundreds of Washington foster youth have spent nights in hotel rooms, government offices and even social workers’ cars when the state has failed to find safe placements for them. The widely-criticized practice takes place in states across the country, leaving troubled teens effectively homeless in the child welfare system meant to protect them.

In a 2021 court filing, licensed clinical social worker and assistant professor at Seattle University Anne Farina warned that if Washington’s Department of Children, Youth, and Families continues to house children in this slapdash manner, “I believe that the children in their care are unsafe and are being harmed.”

Two years later, there is a settlement agreement in place between the children’s lawyers and the state. Change is underway, with a new plan to properly house young people experiencing mental health crises and living with disabilities expected this spring.

But for those children still without proper shelter, practical relief in the form of more suitable and therapeutic housing is still far from imminent.

“Honestly we’re just at the beginning of the reform effort,” said Leecia Welch, an attorney with Children’s Rights who represented plaintiffs in the lawsuit filed in January 2021. “We have a long way to go.”

According to the most recent data released by the Washington Office of Family and Children’s Ombuds, over the past six months, more than 150 children spent at least one night in a hotel or another “emergency placement.”

A spokesperson for the state child welfare agency acknowledged the shortcomings.

“The fact remains, the state does not yet have the needed residential placements for adolescents with the most complex needs,” Jason Wettstein said in an email. “We are working with providers and other state agencies on an ongoing basis to develop the needed placements and supports.”

The Department of Children, Youth, and Families is now seeking feedback from foster youth, parents and advocates as it develops its plan for safer housing.

And by all accounts, many of the children’s circumstances are complex. In an exposé published by InvestigateWest, a 13-year-old autistic boy with a brain injury moved through 39 different foster care placements due to unsafe behaviors at his parent’s home before he ended up sharing hotel rooms with other foster children in Washington.

“It was scary,” he told a reporter. “I was worried all night long about what would happen because I didn’t know anyone there. So I was constantly worrying about if it’s safe to fall asleep.”

“The goal of professional therapeutic foster care is to focus resources on struggling youth with more concentrated and professionalized resources.”

— Jason Wettstein, Department of Children, Youth, and Families

Multimillion-dollar investment in specialized foster care

Washington’s plan to avoid these situations is expected to cost up to $5.2 million, although the state’s budget allocation hasn’t been finalized.

It includes placements for up to 40 children in the homes of foster parents who have received special training to work with high-needs children, and who are paid as professionals to remain at home full time.

For others, the Emerging Adulthood Housing Program will provide supportive beds for young people ages 16 through 20 who meet certain criteria and prefer to live independently.

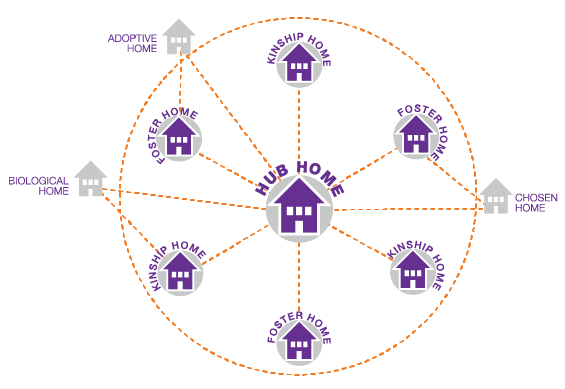

A third option will involve a “hub home,” a model developed by Washington’s nonprofit Mockingbird Society. That approach involves a network of foster families and kinship caregivers who live in close proximity to a more experienced foster parent able to provide support to the other households. The network of caregivers share communal meals, give each other rides and other daily assists, and benefit from having “aunties” and “uncles” nearby. Foster children can spend the night with other families in the hub, providing needed respite for their foster parent and a chance for the teenager to spend some time away in a safe and welcoming place.

Shana Burres, an Olympia foster parent, said that compared with traditional foster care, “the major difference is one of guaranteed community — and a higher level of access to support.”

Burres said the model could work particularly well with teenagers who have experienced trauma and struggle with behavioral challenges and may need extra support.

“Kinship or foster families who are not in a hub need to build that network on their own,” Burres said. In non-hub-model homes, “when you take a placement, the system doesn’t come with that child and say, ‘here is a list of five other licensed homes who can support and who you can reach out to.’”

State officials say more detailed plans to develop the model are in the works. To date, the hubs in Washington have been limited to the Seattle and Tacoma areas.

Regardless of the setting foster youth leaving hotels and offices end up in, the state will need to deploy a “very intensive wraparound system” that provides support for the minors and their caregivers, said Scott Hanauer, a child welfare professional with decades of experience in Washington..

“These kids need daily psychiatric care, and foster parents need a myriad of services to be able to maintain placements with these kids,” he said. “It’s easy for me to say that, but it’s very expensive to do it.”

‘Professional’ foster parents

A key part of the state’s plan will be a “professional therapeutic foster care” program in which children and youth with mental and behavioral health challenges are placed with caregivers who receive specialized training. “Professional” foster parents would care for one child at a time, and at least one of the adults in the household must agree to not work outside the home. The amount is still being decided upon, representatives from the department said, but it is expected to be higher than the typical monthly rates that foster parents in the state receive, which range from $670 to just over $1,600 per month, depending on the child’s age and needs.

“I just needed somebody to show me they cared and to continuously be there.”

— DEstiney Hooks, former foster youth

“The goal of professional therapeutic foster care is to focus resources on struggling youth with more concentrated and professionalized resources,” state spokesperson Wettstein said.

Professional foster parents will be expected to maintain supportive relationships with the child’s family members, facilitate visitation, and participate in shared planning meetings — duties that surpass the typical roles of most foster parents.

The goal is also to have one child in the home at a time, except in circumstances when siblings need placement together.

Of the hundreds of foster youth represented by lawyers in the legal case, Washington child welfare officials anticipate that between 37 and 40 will be eligible for placement in the professional treatment foster care program.

The state will contract with an outside agency to recruit, license and support these “professional” foster parents. They, in turn, will receive not only the higher pay and specialized training, but coaching and respite time.

‘She’s always shown up for me’

Destiney Hooks, now 23, lived in numerous foster and group homes in the Olympia area — many of which felt like “all sorts of kids with different issues” had been thrown together, she said. One placement “felt weird, robotic,” she told The Imprint. “It felt like I was in juvie, but a nicer juvie.” In another, she and her peers had almost no supervision or guidance.

The most comfortable she felt during her time in foster care was a residential program where she developed a close relationship with Tammy Levario, a full-time, live-in caregiver. Levario emphasizes the importance of training and experience in providing a therapeutic environment for youth, but they also need to simply be present.

“The kids deserve to have caregivers who do not work outside the home,” Levario said. “When people are freed up from financial and outside job-related stress, they have the energy and mental and emotional space to give to these young people who need so much.”

Hooks said after her initial skepticism, she eventually learned the power of one dedicated, caring adult who had the ability to talk through any conflicts or issues that arose.

“I just needed somebody to show me they cared and to continuously be there,” Hooks said. “My whole time knowing her, she’s always shown up for me.”

Hooks said when Washington rolls out more therapeutic homes for foster youth she hopes they will be careful and deliberate.

“The whole process is delicate and very fragile, especially with how many youth are in the system and need help,” Hooks said. “And not just any help — they need help that is going to have patience and understanding and open minds.”

Coming next week, how some states have crafted specialized foster care for youth with high needs.