A new statewide plan and local efforts in Los Angeles County aim to avoid family separation in the child welfare system

Mandated reporters have long been counted on to be the eyes and ears of child welfare systems. But earlier this month, Los Angeles County leaders argued that too often, teachers, doctors and police officers cause more harm than good after calling CPS — inviting unfair investigations and the courts into already-fragile families’ lives.

“Parents in Los Angeles deserve access to the services of our County without fear of punishment simply for seeking help,” Supervisor Lindsey Horvath said in a statement last week.

Horvath and her colleagues aim to redefine referrals to child protective services. Their plan shifts from an approach that focuses on mandatory reporting to one that emphasizes “mandated supporting.” The goal is to weed out cases where poverty is the symptom, not physical harm or severe neglect that may warrant a child’s removal from home.

The Los Angeles County approach is part of a wider shift statewide to “narrow the front door” of California’s foster care system.

Under the Family First Prevention Services Act signed into law in 2018 and now rolling out across the country, states can receive Title IV-E Social Security Act funds not just for placing children in foster care, or later into adoption — but for preventing them from ever being separated from their parents.

California is one of 39 states, three tribes and the District of Columbia with prevention plans approved by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The state won’t immediately be able to draw down the federal funding, but other, more immediate efforts to prevent families from entering the child welfare system are also underway. In the coming months, a statewide task force will begin studying how to reform mandatory reporting laws.

The Family First Act represents a new direction for the nation’s child welfare systems, which had previously only been funded by the federal government once children were taken into foster care, and relied heavily on group homes. New emphasis focuses on preventing family separation whenever possible, and keeping children out of institutions.

Officials in the nation’s most populous state welcomed federal approval of the 98-page foster care prevention plan approved last month.

“This approval is a major milestone that I believe will go a long way in furthering California’s efforts to transform how we serve and support children and families in their communities,” California Department of Social Services Director Kim Johnson said in a statement to The Imprint.

‘A very fresh change from the past’

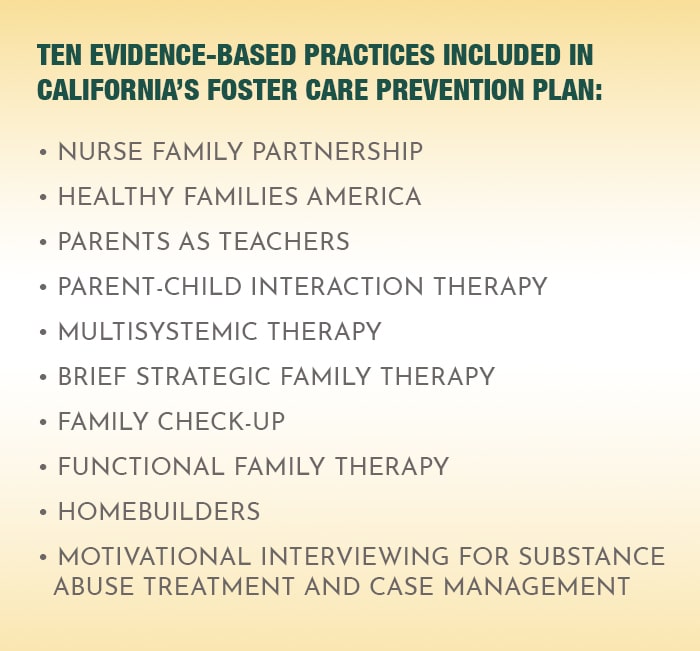

California’s Family First plan centers on three types of help outlined in the law: in-home parenting support, substance use treatment and mental health services. The state also plans to invest in early interventions, like home visiting for parents, and broad-based anti-poverty programs for families who haven’t come to the attention of the child welfare system. Its aims include tackling the over-representation of Black and Indigenous children in foster care, who are far more likely to be the subject of hotline calls and investigations and be taken into foster care than all other children.

A “community pathway” will require counties to provide needy families with voluntary social services that don’t carry the same stigma and fear as receiving help from a social worker who has the power to remove kids from their homes.

Ventura County child welfare director David Swanson Hollinger said although the number of children in foster care in his Central California county has shrunk in recent years, the statewide community-based approach is an “unprecedented” effort, allowing social workers to focus on the most dire cases. “We’re going to be able to support families before things escalate to the level that my system needs to intervene and separate families,” Hollinger said. “We know we still have to place some children into out-of-home care. But ideally, if this is working effectively, we’ll be able to keep more families out.”

Kathryn Icenhower, the executive director of the South Los Angeles nonprofit Shields for Families who has worked for decades with parents managing recovery and the child welfare system, calls California’s new commitment to work with local organizations “a very fresh change from the past.”

Still, there are skeptics.

Sean Hughes, a former congressional staffer–turned child welfare consultant, said that while the community pathway model is a “great concept,” it may be particularly challenging for agencies to provide oversight for children who are deemed at “imminent risk” of entering foster care. Hughes is among those who recommend a more cautious approach in the near future.

“It definitely holds a lot of promise for children and families assessed to be at lower risk,” Hughes wrote in an email. But he added that questions remain about how child safety will be assessed and ensured, and how community-based groups will coordinate with public agencies.

Bridging the gap in funding delays

By all accounts, a fully developed foster care prevention plan will take years to come to fruition.

States nationwide have been slow to launch Family First plans and have them approved. The U.S. Administration for Children and Families estimates that it distributed roughly $29 million last year to such efforts, serving about 6,200 children. That represents a tiny fraction of the roughly 390,000 children now in formal foster care. In the next decade, however, the number of children served by prevention efforts is expected to climb to 672,500.

Among the barriers to prevention plan roll-outs has been a strict requirement that states rely only on programs that have been formally evaluated and meet “evidence-based” standards. Administrative burdens have also hindered prevention plans in many states.

California is no different. In order to track its efforts and start receiving the new federal funds, for example, the state must install a new data system that could be years away. And until the automation is complete, the state can only rely on Family First dollars for administrative costs, not actual prevention services delivered to families.

A spokesman for the California Department of Social Services said the agency has no specific timeline for its completion, though Gov. Gavin Newsom set aside $164 million in his revised budget last week to speed the development process.

Counties can also rely on a five-year, $200 million state block grant, part of a budget package signed into law by Newsom in 2021. The 50 counties and two tribes that have opted into Family First prevention efforts will share those funds, designed to prepare them for the new law and tide them over as the state develops its data system.

Helping vulnerable families in crisis

In the meantime, Icenhower of Shields for Families and Ventura County director Hollinger are coordinating efforts to make legal and legislative changes to mandated reporting that will scale back the number of children referred to CPS.

The approach was first publicly promoted by New York parent activist Joyce McMillan, who defined “mandated supporting” as offering parents access to community-based services that provide food, housing and voluntary treatment programs.

Next month, the state’s Child Welfare Council — an advisory body composed of leading advocates, officials and attorneys — will convene its first task force meeting on the topic, seeking expert feedback and crafting recommendations for the state Legislature.

Some ideas are already circulating. The San Francisco-based nonprofit Safe and Sound calls for tightening the legal requirement of circumstances worthy of a call to CPS hotlines; narrowing the legal definition of neglect and limiting liability for mandated reporters. And a 2022 report written by a panel convened by the Department of Social Services recommended a county-run “community supporting” pilot project, and greater monitoring of racial disproportionality in CPS referrals by mandated reporters.

Icenhower described the challenges in Black communities such as the one she serves, where low-income parents routinely face allegations of abuse or neglect. As a result, many fear accepting help.

“Mandated reporting hinders work with vulnerable families who are in crisis,” she said.

Icenhower added that parents need reassurance that they’re not placing themselves at risk by accepting services, and “the only way we can do that is to be able to demonstrate that we have changed our system of mandated reporting in California.”

Counties outside of Los Angeles are making similar efforts. In the Safe and Sound report, San Diego County’s child welfare director Kimberly Giardina states “the child welfare system has historically been rooted in fear: fear of the rare tragic cases of severe abuse that are missed, and the consequences to the children and professionals involved.”

In the future, she said: “We must resolve the dilemma of keeping children safe and supported without magnifying the feeling of threat, fear, and surveillance often associated with mandated reporting.”