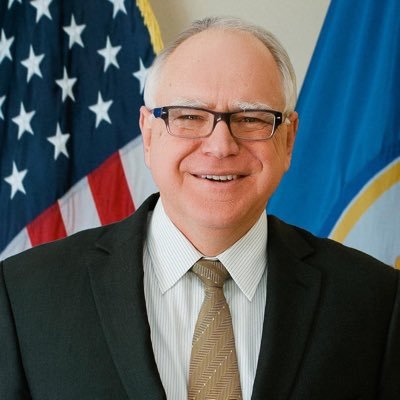

Vowing to make Minnesota “the best state in the country for kids to grow up” in, Gov. Tim Walz (D) is proposing monthly payments for 21-year-olds leaving foster care. The plan is driven by young people and advocacy groups lamenting the current “abrupt end to financial support,” according to the governor’s recent budget recommendation.

The Support Beyond 21 program is being considered by the Minnesota Legislature as some U.S. lawmakers call for more attention to this vulnerable population.

In a letter sent last week to Secretary of the Department of Housing and Urban Development Marcia Fudge, Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D) and Sen. Susan Collins of Maine (R) called out “delays in the delivery of housing vouchers for youth aging out of foster care,” describing homelessness as “one of the most serious hardships that transition aged youth may endure, disrupting social, economic, and physical well-being.”

Klobuchar and Collins want the Housing and Urban Development Department to increase housing security for specific groups of young adults: those who will age out of foster care in the next two years and those who have aged out of care since 2019. The lawmakers are asking for an update on the department’s efforts to ensure transition-aged youth are informed about the resources available to them — “safe and stable housing when they age out of care or otherwise experience disruptions in their housing situations.”

The letter highlighted the story of a Minnesota former foster youth identified as Ada, a young mother of two. The senators’ letter said she had been forced to move through several short-term rentals before a local agency helped her family stabilize. Even with a HUD voucher, Ada had been unable to secure housing because so few landlords were willing to rent to her, “despite her having no history of eviction, poor rental history, or bad credit.”

Gov. Walz’s cash assistance proposal, included in his $12 billion package presented in January, could provide some relief. If approved this legislative session, foster youth enrolled in Support Beyond 21 would receive monthly payments for a year. The amounts, which are still to be determined, would gradually diminish every three months. But participants would be assisted with budgeting and financial literacy to plan for their future independence. The program is expected to serve approximately 175 youth statewide per year.

The precise amount of the payments would depend on the final state budget and the number of youth exiting foster care at age 21, according to the Minnesota Department of Human Services.

Fewer hurdles for youth

Under current state and federal law, teenagers who turn 18 in foster care can opt into extended care until they turn 21, receiving financial, housing and casework support. But they must be working, going to school, pursuing job-training activities or prove they’re unable to participate because of a medical condition. Participants must check in regularly with social workers and judges, and if they fall out of compliance, their eligibility can be challenged in court.

In contrast, financial assistance from Support Beyond 21 would not be based on any specific eligibility requirements other than aging out of extended foster care. Even the financial literacy assistance would be optional, a feature praised by Kristy Snyder, director of the Twin Cities Opportunity Youth Network.

“I’m excited and optimistic about how the shift in requirements could lead us to supporting and thinking about young people and their options differently,” she said.

In 2020, more than 1,100 youth were enrolled in extended foster care in Minnesota, according to most recent state data. But at age 21, this demographic remains at high risk of homelessness, poverty and incarceration.

Foster youth advocates say the need to assist this population of young people is urgent. Half of unhoused people nationwide have spent time in foster care, according to the National Foster Youth Institute. A report published by the Minnesota Department of Health and the Hennepin Healthcare Research Institute in January found that a 20-year-old experiencing homelessness has the same likelihood of death as a 50-year-old in the general population.

“Turning 21 is supposed to be a celebratory moment in your life when you have more freedom and more ability to choose what you want to do,” said Karina Hunt, a coordinator at Connections to Independence, a Minneapolis nonprofit that works to help youth transition to life after foster care. “For foster kids, you turn 21 and all of the support you had is suddenly gone.”

Hunt described the program Gov. Walz proposed as “at least an opportunity for a softer landing.”

She and other advocates say while the Support Beyond 21 program is a step in the right direction, it’s not enough: Young people who have exited foster care often need financial support well into their 20s. Still others may not be eligible, because they did not enroll in extended foster care when they were 18, 19 or 20 due to the program’s strict requirements. For others who have spent years in state custody — despite the offer of additional support — spending additional time in a foster care system that requires ongoing interaction and scrutiny of social workers, lawyers and judges feels out of the question, youth and their advocates say.

A recent Imprint investigation found that only about a quarter of eligible young adults in Texas actually end up in extended foster care — an enrollment rate far lower than other large states.

“Some young people are so traumatized by care that they opt to say no,” Snyder said.

Jessica Rogers, the executive director of Connections to Independence, has also seen the rigid eligibility requirements of extended foster care alienate those 18 to 20, particularly young people who are pregnant or living with a disability. As a result, those former foster youth would not be eligible for the governor’s program that would serve 21-year-olds.

In some states far more extensive proposals to support this population are being considered. Democratic state Sen. Dave Cortese of California has proposed legislation that would extend financial and caseworker support to young adults in foster care in his state until age 26.

A study by researchers at the University of Chicago examining extended foster care in California found that each additional year of support was linked to a host of positive outcomes including education, work experience, the ability to save money and a reduced likelihood of having contact with the criminal justice system.

“It’s tougher than ever for someone at 21 years old to survive on their own, not to mention a young person on day one” leaving foster care, Sen. Cortese told The Imprint in February. “Right now, we’re essentially emancipating young people into homelessness.”

Sign up to receive Minnesota news and updates from The Imprint!