Children’s advocates have published first-hand accounts of 80 young New Yorkers sent to foster care group facilities, in the hopes that sharing their troubling experiences will prompt state officials to act.

“Are You Listening? Youth Accounts of Congregate Placements in New York State,” was released last month by two national child welfare nonprofits, Children’s Rights and Community Impact Advisors and an advisory committee whose members had spent time in foster care settings other than family homes.

While the comments about congregate care quoted in the report were overwhelmingly critical, the researchers acknowledged that the study’s participants “may not be a representative sample of the population concerned.” But they added that they believe the interviews “are demonstrative of youth experiences in New York’s congregate settings. Our analysis revealed clear patterns and consistent themes from youth reports.”

In the report and follow-up interviews with The Imprint, the young people described troubles ranging from fears of violence to unpleasant food.

What stood out for Anthony Robinson was a feeling of “institutionalization.”

“Being on a campus like that alters your reality of what the norm is,” Robinson said in a recent interview. That realization hit him after he left a residential facility in 2019. There was so much to adjust to in a family home: he no longer had staff in control of his day and didn’t need permission for basic needs like eating or going to the restroom.

“They treated it like it was more like jail rather than foster care.”

YOUTH QUOTED IN THE REPORT, “ARE YOU LISTENING?”

The recent report did not name individual facilities in New York, and it included some mention of positive experiences, such as recreational opportunities and lasting friendships with people they met in group homes. But its survey of 80 young adults ages 18 to 28 builds on a growing body of research pointing to poor outcomes for children raised in group facilities. Children’s Rights and their team of researchers and advisors is calling on New York State to reduce the use of congregate care — and ultimately, to eliminate it altogether.

“This report adds to the mounting evidence that congregate placements do more harm than good,” Rashida Abuwala, principal at Community Impact Advisors, said in a written statement. “What foster youth experience at the hands of the system is not right, and they deserve much more — like growing up in home settings with family, friends and community so they can thrive.”

Abuwala wants young people’s voices heard by policy makers and the public. “I hope these brave accounts move New York to do what is morally just and eliminate these harmful placements once and for all,” she said.

“I would describe my creative response as journal entry format with a splash of poetry.”

In many regards, the child welfare industry is aligned, agreeing that out-of-home residential care should be limited to those most in need and for limited periods of time.

Kathleen Brady-Stepien, president and CEO of the Council of Family and Child Caring Agencies — which represents many of the state’s foster care agencies — said her organization is “strongly engaged in advocacy for preserving and supporting families of origin, and to prevent removal and increase supports for children and families in their homes and communities.”

In New York, foster care is overseen by the state Office of Children and Family Services but run locally by counties — and some have moved more slowly than others away from the group care model, which is widely viewed as an option of last resort for most foster children. While the number of foster children living in institutions and congregate care facilities in New York has declined in recent decades, the report states, the proportion has remained higher than the national average and higher than states of comparable size.

Solomon Syed, a spokesperson for the Office of Children and Family Services (OCFS), said in an email that his office reviewed the report and “the experiences it details were disheartening.”

Syed said his office is unable to comment on the individual youths’ experiences, “but we recognize the need for further transformation across the child welfare system, including within congregate care programs.” Syed also described efforts his agency takes to ensure that young people’s voices are heard, including Youth Advisory Board and agency staff who have been in foster care and help recommend policy and practice.

What’s more, he added, “OCFS goes to great lengths to ensure the health, safety and security of children in these settings by conducting regular voluntary agency reviews, which includes meetings with youth to hear their feedback.”

The Children’s Rights report details a range of such feedback. One young person described what it felt like to be patted down and asked to give up their cell phone, money and other personal belongings every time they entered the foster care facility where they were placed.

“They treated it like it was more like jail rather than foster care,” the youth stated. “Most of the kids that were in my home specifically, once they transferred out, they weren’t going back to a regular life, most of those kids were being shipped to jail afterwards. Or, an even worse lockdown facility.”

Others in the report described poor nutrition. One young person suffered twice from food poisoning “because the food was not cooked properly.” On the other hand, “If you don’t eat, they say, ‘Oh, you’re self-harming yourself, we have to take you to the hospital.’”

Some survey respondents said the allowance they received wasn’t enough to buy proper clothing, particularly winter clothes. One young person said a fellow resident who didn’t have a jacket one winter caught pneumonia and died. Others said toiletries such as hair products were culturally inappropriate, insufficient or caused allergic reactions.

Nearly all the young people who spoke to researchers said they felt they did not receive proper care when they were sick, injured or assaulted by peers — a far-too common occurrence in group facilities. Many mentioned that staff were reluctant or even refused to take them to a doctor.

“They had prescribed me sleeping medication for my ADHD because they noticed I was an insomniac,” one respondent said. “And the thing about it is, they don’t really correspond with the doctor. They make up their own rules. So, while I was supposed to be taking two pills, they were giving me five.”

Those who contributed to the report consistently shared accounts of harsh punishments, including physical restraints and being separated from other kids.

Jonathan DeJesus, who left foster care in 2021, said children were restrained by staff during heightened, chaotic incidents, such as fights among residents.

“You can’t expect 17 other youth with different backgrounds, different traumas, sharing a room — you throw them in there, not supported — to be kind to each other,” DeJesus said in an interview. “The bullying, that’s what leads to restraints. It creates a hostile environment.”

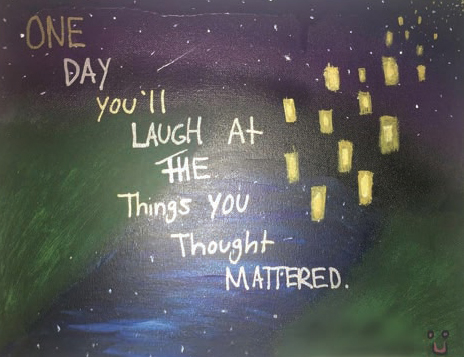

“I painted this when I was in a group home. They had a recreational therapist come to the home on a weekly basis. She was really nice and helped me express myself through art. During that time I was going through a lot of difficulties, especially my mental state. That day I decided to paint myself a message that little did I know I would look back at it today and actually smile and laugh at what I did thought mattered in those moments.”

There were roughly 2,000 children in out-of-home group care in New York in 2021, a 13% rate that exceeds the 9% national average, according to the researchers’ analysis of data from New York’s Office of Children and Family Services and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. That rate is among the highest for states with large foster care populations.

State officials say the current rate is just above 14% of all foster youth.

Among states with the largest foster care populations, New York had the second-highest congregate care placement rate in 2015, the third-highest placement rate between 2016 and 2019 and the fourth-highest placement rate in 2020, Children’s Rights reports.

Still, from 2010 to 2020, the number of New York foster youth in group settings decreased by 62% — a significant decline.

But those who remain are disproportionately young people of color. Black children in New York make up 15% of the general child population but 57% of foster children in group settings.

Although the state’s use of congregate care is on the decline, Children’s Rights and the advisory committee want the model eliminated. Until then, they are calling for a ban on the use of restraints and other punitive measures, better evaluation of facility standards and staff conduct, and a hotline for children to report maltreatment.

They also want policymakers and child welfare leaders to better prioritize in-home support, mental health care and financial aid for struggling families so they can care for their children within kinship networks — avoiding group settings altogether.

Although the facilities where the survey respondents had been placed were not identified in the report, 14 of the 36 youth interviewed spent time at the New York City Children’s Center, run by the Administration for Children’s Services. The Manhattan facility was originally built as the morgue for Bellevue Hospital. It has undergone numerous renovations over the decades it has been used as an intake facility for children awaiting a foster care placement.

Officially named the Nicholas Scoppetta Children’s Center, its late namesake and one-time Children’s Services commissioner once vowed it would never become a long-term shelter.

“We are absolutely, unequivocally opposed to that,” Scoppetta told the New York Times in 2001.

But in fact it has become an emergency shelter where children remain too long in limbo. Young people reported staying there anywhere from a week to several months, some describing a situation that was “overcrowded, felt unsafe, and was unsanitary (with multiple reports of mold and rodents),” the report authors state.

The report also noted a lack of adequate staff supervision that led to bullying, assault and theft among the children.

“Participants shared several stories of youth engaging in sex-work and alcohol and drug use while at the Center,” the report stated. “One youth shared that she was out of school ‘for months’ while awaiting a transfer from the Children’s Center.”

A spokesperson for the city agency said it has made “significant” improvements over the last few years, including adding child care and nursing staff, youth programming and facility upgrades. Current improvement goals include providing a “safe, trauma-informed welcoming environment.” The agency is also working to reduce the number of children placed at the center as well as the time they spend there. The goal is “to find a safe and supportive foster care placement setting that meets the child’s needs until he or she can return home or another permanency arrangement is finalized,” the spokesperson said in an email.

“We continue to listen to the youth in our care, and take steps so they feel safe and supported during what is a challenging time in their lives,” she added.

Still, current and former foster youth say far too many have already suffered lasting impacts. Michelle Perez is a member of the Children’s Rights advisory committee who left foster care at age 18, almost a decade ago. Along with Robinson and DeJesus, she is now advocating for other foster youth sent to group settings.

“This report is really for the voiceless. The system can be changed when the right people are listening,” Perez said. “It’s not for us anymore — we lived it. I hope it’s able to open doors, to shine a light in places that don’t have that.”