A plan released by the Los Angeles County Probation Department this week calls for shuttering six of the county’s juvenile detention camps over the next two years.

The proposal would also relocate girls currently housed in the other camps into the eagerly awaited Campus Kilpatrick facility, a move that drew the ire of some commissioners at today’s Los Angeles County Probation Commission meeting.

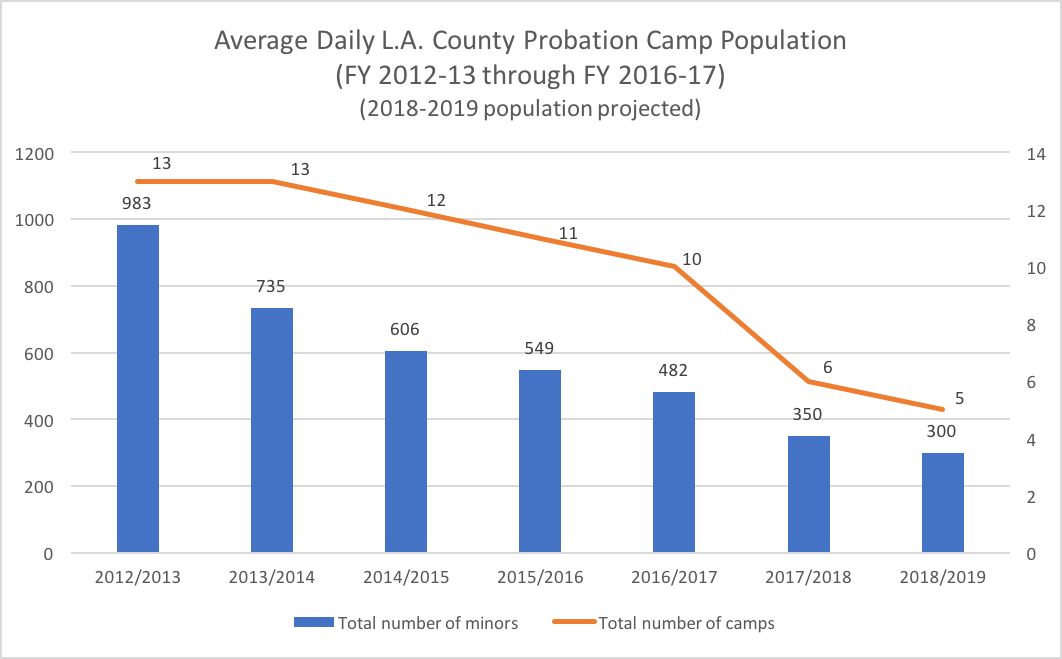

L.A. County currently has 10 juvenile camps open, though two camps—Kilpatrick and Scudder—are currently being renovated. The county’s network of camps, which totaled 13 in 2014, were built to hold 1,469 youth. But the number of youth incarcerated in them has plunged in recent years.

In the 2016-2017 fiscal year (FY), the average daily population of youth housed in camps was 482, down by 51 percent from FY 2012-2013. L.A.’s Probation Department projects that number will shrink further—to just 300—within the next two years.

According to the Probation Department plan, which was first presented to the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors last month in a closed meeting, Camp Gonzalez, Camp Scobee and Camp Jarvis will be closed next year, followed by Camp McNair and Camp Onizuka in 2019. Under the new plan, seven camps would remain open, including the Dorothy Kirby Center, a Probation facility for youth with mental health issues.

Chief Deputy Probation Officer Sheila Mitchell cited the soaring costs of youth incarceration and far-flung locations of the camps as reasons for the consolidation effort. The most recent estimate of the cost of a year’s worth of incarceration in one of L.A. County’s camps is $247,000 per youth.

Mitchell said that in addition to ongoing maintenance costs for the aging facilities, the county is trying to preserve camps that are located closer to the homes of detained youth, helping to facilitate family reunification efforts.

“Geo-mapping gives you an idea where our kids currently live,” Mitchell said. “Our kids really live around where our Central Juvenile Hall is in L.A. They don’t live up north. Why that’s important is that we really wanted to focus on efforts on re-entry.”

Advocates have long called for the closing of many of the county’s juvenile halls and camps, citing high rates of recidivism, poor conditions at the camps and uneven access to services and programming.

Though the camp closures were met with excitement by many advocates, the Probation Department’s decision to place girls alongside boys in its soon-to-open Campus Kilpatrick came under fire.

On July 3, the county will open the doors at the refurbished camp in Malibu, a small-group facility that county officials hope will serve as the centerpiece of the L.A. Model, a therapeutic approach to youth in juvenile detention described as “a culture of care rather than a culture of control.”

Campus Kilpatrick has been designed over the past three years with only boys in mind, but that will change under the proposed Probation Department plan. The number of girls in L.A.’s juvenile camps has rapidly dwindled and now stands at approximately 25, according to Mitchell. Campus Kilpatrick would begin housing 24 of those girls alongside boys on January 30, 2018.

Probation Commissioner Jan Levine raised concerns about whether the county had done enough research about the consequences of bringing girls into a facility that has been planned around the needs of boys in the justice system.

“I don’t think it’s something that should just be slapdash,” Levine said. “It just raises a whole host of other issues for staff, for the boys, for the girls, and those really need to be aired.”

Several commissioners expressed concern that Kilpatrick’s carefully planned therapeutic design would be compromised, or that the needs of girls in the justice system—who tend to be far more likely to have experienced sexual abuse than boys—would be lost in the process.

Mitchell said that very few girls in the justice system are commercially sexually exploited children These youths rarely end up in juvenile detention and are more often are diverted to the well-regarded Succeeding Through Achievement and Resilience (STAR) Court program that seeks treatment rather than incarceration, she said.

Placing girls alongside boys occurs at several juvenile detention facilities across the country, and even at the Dorothy Kirby facility in Commerce. Mitchell is hopeful that a current effort to assess girls detained at Camp Scott and the Dorothy Kirby Center will further reduce the number of girls placed at juvenile camps.

“We believe some of the girls at the camps should never have been at the camps in the first place,” Mitchell said.

The question of how the county could use the potentially vacant facilities and cost savings related to the camp closures remains unknown for now. Mitchell said the county is looking at using one of the camps scheduled for closure as a job placement center, while commissioners discussed the possibility of using another as a facility to help youths with serious mental health issues.

The Probation Department is still discussing how it will re-direct savings from the closure of the expensive juvenile camps. Many advocates are hoping that savings from the consolidation of juvenile detention facilities could help fund the county’s developing diversion plan, which aims to prevent at-risk youth from entering the justice system.

According to Mitchell, there is also some interest in working with the philanthropic sector to better serve youth outside of locked facilities.

“We’ve already been meeting with some foundations and looking to form public-private partnerships to invest those savings into the community to build additional capacity to serve young people,” Mitchell said.

The plan is expected to be considered by the Board of Supervisors in the coming weeks.