A county-led forum in Los Angeles marks a pivotal moment in the application of data analytics and risk modeling to child abuse.

On Wednesday, July 22, Los Angeles County’s recently formed Office of Child Protection will hold a community forum to discuss the simultaneously disquieting and promising prospect of using “big data” to help determine which children are the most likely to be abused.

The question of whether child welfare agencies should apply a statistical discipline called “predictive analytics,” which uses data to infer what may happen in the future, has sparked a now global debate weighing civil liberties, racial profiling and the alluring potential of accurately directing limited public funds to better protect children. Despite the understandable fears that come with applying an algorithm to the very human question of family dysfunction versus family strength, evidence from its use in other child welfare administrations shows promise.

But a major sticking point still remains: Using data from one’s past to predict future behavior could have unintended consequences, the most worrisome being that new risk modeling tools would focus needless negative attention on poor families of color.

“We don’t need another tool that says these kids are at risk,” said Dr. Matt Harris, the executive director of Project Impact and “co-convener” of the Los Angeles County Community Child Welfare Coalition, a 50-member alliance of youth service providers. “We have enough of that. After the assessment is made, what are the support services to rescue kids?”

This volatile mix of hope and fear has heightened the significance of the Office of Child Protection’s fast-approaching meeting. In no uncertain terms, the tenor of the discussion on Wednesday will not only have implications for how “predictive analytics” is applied in child abuse detection in Los Angeles, but will also influence the worldwide risk modeling debate.

Los Angeles’ Risk Modeling “Proof of Concept”

Los Angeles County is home to the largest child welfare system in the world. Last year, child abuse investigators working for the sprawling Department of Children and Family Services (DCFS) fought through a crush of 220,000 reports of child abuse.

In an effort to help these harried investigators make better decisions, the department contracted with SAS, the world’s largest private software firm, to test out risk modeling.

The experiment, dubbed AURA, or Approach to Understanding Risk Assessment, tracked child deaths, near fatalities and “critical incidents” in 2011 and 2012. The firm called these very rare and tragic happenings “AURA events,” and looked six months back in the histories of those children and families to find reports of abuse, which they called “AURA referrals.” Using a mix of data including, but not limited to: prior child abuse referrals, involvement with law enforcement, as well as mental health records and alcohol and substance abuse history, SAS statisticians created a risk score from one to 1,000, wherein high numbers demark high risk.

The next phase involved applying those risk scores to DCFS referrals in 2013 to gauge if AURA was any good at identifying which kids were most likely to be victims of severe and even deadly abuse.

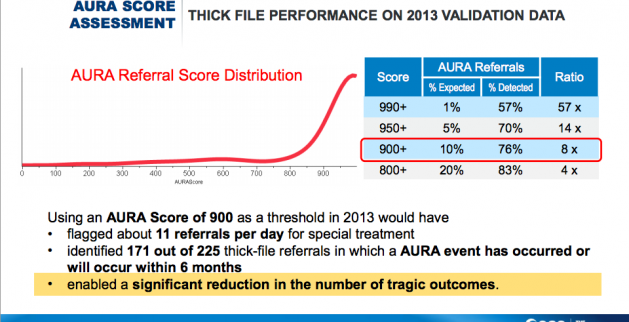

The Project AURA Final Report, a PowerPoint presentation created by SAS and dated Oct. 14, 2014, stated that if the department had used the tool in 2013, it would have “enabled a significant reduction in the number of tragic outcomes.”

A slide from the SAS final report on AURA, shows results in the tool’s ability to identify risky referrals.

The report went on to explain that if AURA had been used with cases that had a score of 900 or more, it would have flagged “about 11 referrals per day” for “special treatment.” Among the roughly 4,000 flagged reports in 2013 were 171 wherein a child experienced one of those rare “AURA events” within six months.

That means AURA identified 76 percent of the cases that would or did result in a child dying, nearly dying or being severely injured at the hands of a caregiver.

But as seemingly powerful as SAS’ experiment proved, DCFS Public Affairs Director Armand Montiel pointed out that there were some clear costs and benefits.

“This may be true,” Montiel said of SAS’s claim that it identified 171 critical incidents in an email sent to The Imprint. “But it [AURA] also identified 3,829 ‘false positives’ meaning – if our math is right – 95.6% of the time, there was no subsequent critical event. So, we must be very careful not to, in any way, indicate that AURA is a predictive tool.”

“Although we know neither AURA nor any other tool can predict which families will abuse their children,” Montiel continued, “we hope AURA, or a similar tool, will help us better identify families at risk of abuse, so that we and the community can help our families prevent abuse from occurring.”

Jennie Feria is an executive assistant to DCFS Director Philip Browning, and the lead on AURA. While Feria was duly impressed with the results, she also said that AURA was only a “proof of concept,” and that the department was far from deploying any kind of risk modeling tool into the community.

“I think it is a much needed conversation,” she said about the Office of Child Protection’s upcoming meeting. “We need to bring along everybody so we can take this journey together and have more understanding about the positive and possible negative outcomes.”

Despite DCFS’ assurances that predictive analytics has yet to take root in Los Angeles County, the mere idea of “predicting” which children will be abused has conjured up images of child protection workers descending into poorer black and Latino neighborhoods armed with “data” that will speed removal of those children.

Civil Liberties and Profiling

The most vocal concerns have come from the aforementioned Los Angeles County Community Child Welfare Coalition, which represents an increasingly organized confederation of large non-profits, grassroots organizations and churches serving families in the communities most impacted by child abuse, and subsequently, intervention by the child protection system.

The coalition articulated their worries in a 10-point email sent to the Office of Child Protection on July 16, which stated that: “Predictive analytics could be used to create maps and information used to further marginalize certain populations or justify disproportionality in the Child Welfare system, based on race and bias.”

Former County Supervisor Zev Yaroslovsky said, in an interview last week, that he too had been concerned about the idea of “predicting” child abuse when he read a story about data analytics and risk modeling that ran in The Imprint in October of last year.

“It’s about prevention, not prediction,” Yaroslavsky said. “Prediction is the wrong word. Intervening on someone where there is no problem because there might be a problem runs against American values.”

Nick Ippolito, assistant chief of staff to Supervisor Don Knabe, said that his boss had been interested in seeing AURA or something like it implemented in the county but that concerns about “civil liberties” and “profiling” had slowed county movement towards deploying a child abuse risk-modeling tool.

“I totally agree with people that the integrity of families should be protected, and that people’s rights are protected,” Ippolito said. “But God Damnit, if a kid is in serious trouble, we have to do anything we can to protect that child.”

The Global Rise of Risk Modeling

Risk modeling has already taken root in public services outside child welfare, and while still in its infancy, has rapidly spread to child welfare administrations throughout the United States after having been pioneered in New Zealand.

Los Angeles County’s Department of Social Services contracted with SAS to create an AURA-like tool to detect fraud in its child-care program. In Florida, another much smaller data analytics firm has created a predictive tool, which has shown promise in identifying those juvenile offenders who are most likely to recidivate.

When it comes to child welfare, the most notable examples of risk modeling can be found in Florida, Pennsylvania, Texas and New Zealand.

Florida’s Rapid Safety Feedback (RSF) tool was developed in Tampa’s Hillsborough County after a spate of nine child deaths from 2009 through 2012. The Hillsboro model, developed by Eckerd, a private child welfare services provider, looked retrospectively at child abuse cases to determine risk factors for abuse. Since RSF was launched in 2013, Hillsborough County has been spared any child deaths. While the addition of a sizeable number of child abuse investigators in 2014 and the anomalous nature of child deaths makes the absence of child death impossible to attribute to RSF alone, the tool has caught the attention of other jurisdictions. Eckerd is working to apply its predictive analytics model in Connecticut, Alaska, Oklahoma, Nevada and Maine.

Allegheny County, Pennsylvania is in the early stages of developing a risk-modeling tool of its own. Unlike the Eckerd model, which relies on child welfare data alone, the county’s Department of Human Services is pulling data from its heavily integrated data system.

“We’d use all available data, including when dad was in jail three years before that call,” said Allegheny County Human Services Deputy Director Erin Dalton in an interview with The Imprint in April.

In Texas, the Departments of Family Protective Services and State Health Services analyzed three years of data from both departments, and released a report in March sharing their findings. In the report, officials indicated their intent to develop child abuse programs that target prevention, intervention and education in the areas of most need. As in Allegheny County, Texas’ nascent predictive analytics tool pools data from multiple data sets to determine which children are at greatest risk.

But for all the action in the United States, New Zealand is the furthest along, on the cusp of launching a risk-modeling tool nationwide that would be deployed when a call comes into its hotline. In 2014, the island nation fielded 147,000 allegations of child abuse. Like Allegheny County, the model that New Zealand is developing relies on data from multiple agencies to make predictions. While embraced at the top levels of government, there have been some fears that native Māori peoples, already disproportionately represented in the child welfare system, will be heavily targeted by a predictive analytics tool.

A Moment of Embarkation

In late June, Fesia Davenport, the interim director of the Los Angeles County Office of Child Protection, visited a skeptical group of leaders from the Community Child Welfare Coalition on Normandie Avenue in South L.A.

Davenport, unable to answer all the group’s questions about how a risk-modeling tool could be applied in Los Angeles, promised to continue the conversation. With an expediency not expected from county government, Davenport’s office organized this Wednesday’s community forum, and stacked it with panelists who are on the leading edge of the field.

“I told the group [of community coalition leaders] that we want to separate concept from implementation,” she said in an interview after the late June meeting. “Do we know what the marriage of big data and risk assessment is? Are we saying those two mediums should never meet?”

Members of the coalition, who have been outspoken in their mistrust of DCFS leadership, of which Davenport was a part before taking over the Office of Child Protection, expressed appreciation that their concerns would be met with such a high level discussion.

“I think it is a breath of fresh air,” Dr. Matt Harris of Project Impact said. “It is one of the first times we have felt the county has responded with this level of integrity to our concerns as first line responders at the ground level with the community.”

Among the panelists are Jennie Feria of DCFS; Emily Putnam-Hornstein, an associate professor at the University of Southern California’s School of Social work who is consulting on Allegheny County’s risk-modeling project; and Rhema Vaithianathan, a professor at the Auckland University of Technology and the lead researcher developing New Zealand’s predictive risk-modeling tool.

So it is.

On July 22, Los Angeles will host a conversation focused on the point of friction between the dizzying computation of sophisticated machines and the well-being of children.

Data analytics has, in a few short years, penetrated the highest levels of thought in child welfare, and roiled the field. The speed with which risk modeling has gained popularity, and the power that so-called “big data” holds, suggests that we are at a moment of embarkation. A moment that will, if guided with a meek hand, change not only how to address child protection, but moreover how to go about the hard business of social change.

NOTE: Heimpel will moderate the panel on July 22.