Any serious attempt to reduce child maltreatment, and its devastating effects on countless children who may or may not interface with child protective systems, requires a clear point of entry.

On Nov. 12, child welfare researcher Emily Putnam-Hornstein, showed off the results of two years of work funded by the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation at a small convening at the University of Southern California, which, if given broad audience, should have long lasting, multi-sector policy implications.

“When you have millions of records, there are a lot of ways you can cut the data,” Putnam-Hornstein said in front of a group of 30 to 40 people that reflected the child welfare advocacy, philanthropy, education and public administration communities.

What she and a research team that included Barbara Needell, Bryn King and Julie Cederbaum “cut” was a series of five elegant issue briefs outlining the results of a linkage of roughly one million Child Protective Services records with 1.5 million California birth records. The briefs outline the maltreatment histories of pregnant and parenting teens — particularly those in foster care — in California and specifically in Los Angeles County.

While the rich, descriptive data contained in each brief warrants deep investigation and action, one finding left everyone in the room nearly gasping, and the policy-minded grasping for an effective strategy to reply to an undeniably clear call for intervention.

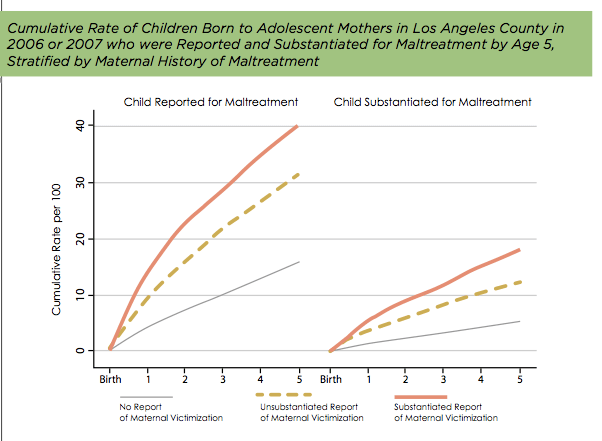

Putnam-Hornstein identified 24,767 teen mothers ages 15-19, who had a child during 2006 or 2007 in Los Angeles County. They then traced the child maltreatment histories of those mothers back to their tenth birthdays, while tracking the instances of child maltreatment for their children up to age five.

The findings are startling. For babies born to teen moms who were victims of alleged abuse or neglect while they were children, 30.7 percent went on to be alleged victims of abuse themselves, while nearly 12 percent were victims of substantiated abuse or neglect.

When accounting for mothers who had been victims of substantiated abuse or neglect the numbers shoot up further, with almost 40 percent of their children linked to reported maltreatment while 18 percent suffered substantiated maltreatment.

Amy Lemley, policy director of the John Burton Foundation, was tapped by the Hilton Foundation to present a series of policy recommendations to complement the release of the research. Among Lemley’s six bullets was a call to increase child care for pregnant and parenting foster youth.

“According to the report, the rates of substantiated abuse and neglect among children born to teen mothers with a history of reported or substantiated maltreatment were a full two to three times higher than the rates of children whose teen mothers had no history of involvement with Child Protective Services,” Lemley wrote in the short memo circulated at the convening. “This dramatic effect highlights the need to provide intensive support services to parenting dependents… One such support is access to affordable high-quality child care.”

During the last legislative session, Lemley’s John Burton Foundation joined with two other co-sponsors (the Children’s Law Center of California and Public Counsel) to run a bill that would have given parenting foster youth priority status to subsidized child care. This provision was stripped from the final legislation, largely because of the already heavy over-utilization of subsidized child care made available to “low-income” parents in California, Lemley said.

“It was a little too much too early,” Lemley said of the bill during the meeting at USC, while pointing out that the new research creates an unparalleled opportunity to drive new policies to help this population. “This is the end zone ball smash,” she said in a separate conversation. “This is the Midwest Study[1] for pregnant and parenting foster youth.”

She recommended expanding childcare for parenting foster youth in two ways. First, by accessing federal funds available for child care intended for foster parents. And second, by expanding eligibility requirements for youth wishing to opt into extended foster care to include those who are pregnant or parenting.

Currently, foster youth have to show that they meet one of five criteria — including college attendance and employment — to be eligible for extended foster care.

Greg Rose, the deputy director of the California Department of Social Services who oversees child welfare, promised to examine whether expanding foster caregiver related child care to youth was possible, while Martha Matthews of Public Counsel questioned whether expanding eligibility for extended care was the right approach.

This is only the start.

[1] The Midwest Study, conducted by Mark Courtney and colleagues at Chapin Hall at the University of Illinois, tracked the outcomes of transition-aged foster youth over many years in three Midwest states. The multi-wave longitudinal study is credited with driving deep policy change to benefit transition-aged youth, most notably informing the extension of care provisions offered in the landmark Fostering Connections to Success and Increasing Adoptions Act of 2008.