New York City’s Mayor Bill de Blasio is big on fairness. In an address last year, he laid out ambitious plans to make New York “the fairest big city in America.”

New York City’s Mayor Bill de Blasio is big on fairness. In an address last year, he laid out ambitious plans to make New York “the fairest big city in America.”

The city’s jails, schools, hospitals and even its waste facilities have all adopted strategies during his tenure to reduce inequities for historically disadvantaged communities. Now, the foster care system is expanding its efforts to address longstanding disparities, especially for black children whose presence in the system is roughly double their share of the general population.

The foster care and juvenile justice system’s 12,000-person workforce, mostly housed at the city’s Administration for Children’s Services (ACS), has begun taking a new course exploring how subtle, unconscious prejudice – often called implicit bias – influences everything from interactions with co-workers to high-stakes child abuse and neglect investigations.

It’s part of ACS’ recent focus on “lifting the value of racial disproportionality to the value of safety and risk within our system,” says David Peters, ACS’ head of the Office of Equity Strategies (OES). That focus was prompted in part by a legislative package De Blasio signed in September of 2017, which mandated training on implicit bias, discrimination and structural inequity at city agencies.

Peters’ OES was formed in 2017 to begin implementing the law, and helped develop the new bias course with the ACS’ Workforce Institute at a cost of about $190,000. The course was piloted throughout the summer and rolled out in late November.

Peters says the agency is also preparing to expand citywide an alternative intervention for families accused of child maltreatment whom the agency believes to be lower-risk, called Family Assessment Response (FAR). The strategy, also known as differential response, involves offering support services to parents in lieu of a formal child welfare investigation. One expert-compiled database of child welfare interventions lists FAR as a “promising” program for reducing racial disproportionality. (The strategy has also been the subject of heated debate on whether it increases risks to children. The Chronicle of Social Change’s publisher Daniel Heimpel publicly questioned the approach several years ago.)

ACS started piloting FAR in Queens in 2012, and Brooklyn in 2016. The agency declined to share more details on the expansion, but an ACS source said there is an estimated 5-year plan to take the program citywide.

“Mayor de Blasio is holding all city agencies accountable for racial equity applications in their departments and Commissioner Hansell should get credit for institutionalizing the tenements of racial equity and having a non-bias lens at ACS,” said Dr. Sophine Charles of the Council of Family and Child Caring Agencies, who has worked in and around the city’s child welfare systems for nearly two decades. “The challenge now is operationalizing it, to see it on the front-line staff level.”

“We have not seen the trickle-down impacts that we’re hoping for yet,” she added.

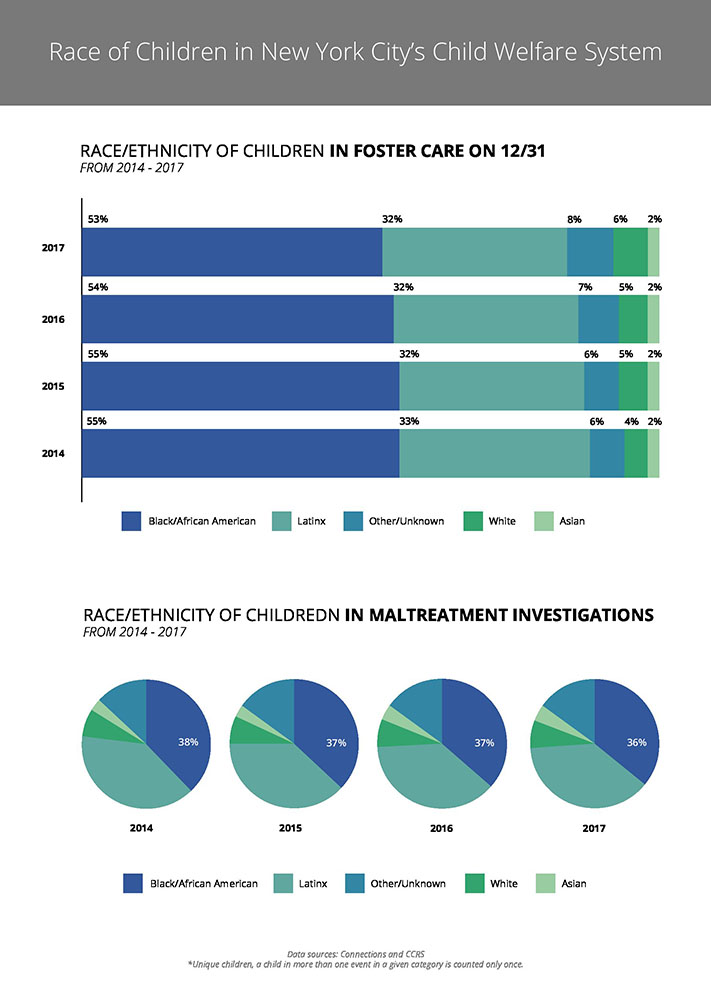

Fifty-three percent of the roughly 9,000 children in the city foster care system identified as black in 2017, according to state data. Yet, only around a quarter of all New Yorkers younger than 18 are black. The numbers are less severe further upstream in the system: 36 percent of all city children whose parents had been credibly accused of neglect or abuse were black in 2017. By contrast, the city’s white, Latinx and Asian children were all underrepresented in foster care compared to their share of the total population.

These gaps have endured in cities like New York and Chicago as their foster care populations have shrunk dramatically since the late 1990s, and even as the share of black children in the foster care system nationwide dropped from 26 percent to 21 percent between 2006 to 2016.

“We take care of everyone else’s kids, but they tell us we can’t take care of our own,” commented attorney and former social worker Helen Higginbotham, who is black, at a recent gathering of accused parents and parents’ rights advocates at The New School in Manhattan.

Nationally, some child welfare professionals say the more important disparity is data indicating black children experience maltreatment at higher rates.

“A powerful coalition has made ‘racial disproportionality’ the central issue in child welfare,” wrote the Harvard Law School professor Elizabeth Bartholet in a 2009 law review article arguing against prioritizing the issue. “The evidence indicates that black children are in fact disproportionately victimized by maltreatment. This is to be expected because black families are disproportionately characterized by risk factors associated with maltreatment, including severe poverty, serious substance abuse and single parenting.”

Advocates for parents counter that child maltreatment data is skewed by subjective evaluation criteria embedded in state laws for neglect and abuse. They say some black communities today inherited decades of racism and poverty that mandated reporters, including teachers and doctors, conflate with bad parenting. Government lawyers then file flimsy “neglect” charges against the parents, rarely making more serious physical abuse claims.

“If an entire system never says once that a child is removed for being poor, yet poor people are consistently surveilled and targeted, then you are going to have a system that penalizes poor people with alarming efficiency,” says Tricia Stephens, an assistant professor at Hunter College’s Silberman School of Social Work, who studies the experience of New York City parents involved in the child welfare system. “And where race and poverty are closely paired together, you are absolutely going to see black children in disproportionate numbers.”

ACS leadership says their new bias training is part of a deliberate effort to reduce black overrepresentation and bias.

“We’ve recognized there’s disproportionality, but I don’t think there was ever a concentrated effort to address it like there is now,” says Ancil Payne, a longtime ACS employee who is now an assistant commissioner and a volunteer on the agency’s Racial Equity and Cultural Competence Committee, which helped develop the bias course. “The entire city is looking at how they can affect disproportionality across all systems.”

An online component of the course focuses on the role unconscious bias plays in interactions with co-workers, and will be required for every ACS employee. It will also be open to employees at the dozens of nonprofits that provide services to ACS-involved families.

The 90-minute online seminar features a full-screen slideshow depicting racist incidents in the workplace. You watch a white co-worker at a social service agency suggest to a black co-worker that she’s identifying too strongly with the at-risk black teens they serve. A supervisor, who appears to be Asian-American, moves the conversation forward without pointing out the (possibly inadvertent) racist slight.

The next slide asks users whether or not this was an articulation of biased thinking by the white co-worker — one of several varieties of what the pioneering social psychiatrist Chester Pierce dubbed as “microaggressions.” In another scenario, a white male employee tells a black female co-worker that he thinks bias trainings are pointless since he isn’t racist. A narrator then suggests possible avenues for the black worker to handle this scenario.

The course pairs these scenes with a review of the scientific consensus that subtly bigoted remarks and decision-making, deliberate or not, can cause psychological and professional harm to minorities and women in the workplace. A day-long follow-up classroom session focused on bias in interactions with at-risk families will be required only for caseworkers and their supervisors.

Stephens, echoing a half-dozen other advocates who spoke to The Imprint, says she appreciates the agency’s intent with the new course, but questioned whether it lays too much responsibility at the feet of child protective staff who are trained to follow strict investigative protocols. “[The course] is suggesting an individual is most responsible for what an institution is doing,” she said. “Institutional bias will ensure the perpetuation of disproportionality long after trained front-line workers have moved on.”

Payne stresses that the course isn’t a panacea.

“This isn’t about undoing bias, it’s about understanding how it influences decision-making and how it influences your interactions with families we serve and colleagues you work with.”

The agency is assessing the training via pre- and post-course quizzes, satisfaction surveys, and action planning for participants. Asked if the agency has hard number targets for unskewing the racial distribution in its systems, ACS’ Peters said: “I wouldn’t say there aren’t numbers we want to hit.”

Along with the new course and the FAR rollout, the agency is developing a comprehensive racial equity plan that will examine data on what could be contributing to disproportionality in each of its divisions. Peters says it should be available publicly by July 1.