New data on the educational outcomes of foster youth points to both the simple and complex challenges we face in shrinking the achievement gap for California’s neediest students.

Today, a new study on the educational outcomes for California students in foster care comes to an expected conclusion: they fare worse than their peers.

Of the nearly six million California children in K-12, San Francisco-based research group WestEd focused on the 43,140 students it identified in foster care. The dropout rate for these children stood at 8 percent in the 2009-10 school year, twice the rate as their non-foster peers.

This is no departure from prior research on academic outcomes for foster youth, and doesn’t come as a surprise to child welfare professionals and educators. According to the study, just under half of foster youth will pass the California High School Exit Exam by 10th grade, while 76 percent of the general population and 66 percent of economically disadvantaged students will.

It is easy to come up with explanations for this stark opportunity gap; much harder to execute on solutions.

The reasons are well known. Too many school moves. Lack of communication between education and child welfare. No single person solely responsible for the academic achievement of foster youth. Trauma and its effects on education. Proximity to quality schools. Money.

The supposed remedies to the more obvious of these problems have been codified into state and federal laws. And the more insidious problems — the trauma that befalls certain children, and the unfair distribution of poor schools in poor neighborhoods – beg larger solutions.

But in sum, our legislative efforts and collective acknowledgement of structural injustice, continue to leave foster children at plain disadvantage. We are 30-years into California’s saga to improve the educational outcomes of foster youth and we are still talking about dismal educational outcomes.

In the early 1980’s, California’s Department of Education, as authorized by state legislation, expanded its Foster Youth Services Program (FYS). Even today, the basic premise behind the program is novel. Namely, that a public educational agency has its own unique responsibility to students in foster care.

Through FYS, which places workers in California’s 58 County Offices of Education to oversee the academic journeys of foster youth, the state took a national lead. But still, public education, from the federal Department of Education down, is loath to bear its share of responsibility for the education of foster youth.

And while FYS has shown clear educational gains for the students it has touched, the program is far from perfect. With liaisons overseeing counties as vast, complex and far-flung as San Bernardino, Los Angeles and Siskiyou there are simply too few workers to make the population-level impact needed to combat the dismal outcomes reported today.

Facing the chronic specter of numerous school moves for foster youth and lengthy delays in the transfer of transcripts and credits, advocates pushed lawmakers to introduce comprehensive legislation to fight both. Assembly Bill 490, which became law in 2004, compelled local educational agencies to transfer student records in a timely manner and ensure transportation to the school of origin if a school move was deemed in the best interest of the child.

This has helped, but is far from sufficient. Only about two thirds of students in foster care made it through an entire school year without a school move, as compared to 90 percent of their similarly disadvantaged peers, according to the WestEd study. Delays in the swift movement of academic records and credits persist. For children with the benefit of a lawyer carrying a reasonable caseload, a quality guardian ad litem or an educational advocate, the law is great. But state-level budget cuts have gutted the juvenile courts’ capacity, and there are simply not enough guardian ad litems or educational advocates to serve all of the state’s foster youth.

Add strict federal mandates on child welfare’s responsibility in the education of foster youth, and a new federal law easing social worker access to foster youth records, and you have an as-yet-complete, but comprehensive, legal framework to do better by students in foster care.

But, beyond the underwhelming follow through on thoughtful legislation, are problems outside the scope of either foster care or education.

According to the study, foster youth are five times as likely as their peers to be diagnosed with an emotional disturbance. The problem is that the terrifying maltreatment and the development-choking neglect that children must survive before ever entering foster care have educational repercussions that neither system may ever overcome.

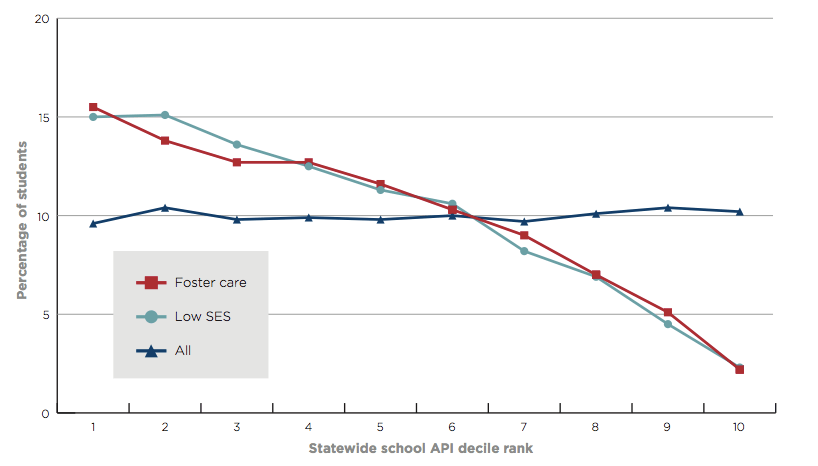

Foster youth, like their economically disadvantaged peers, attend poorly performing schools at higher rates than students in the general population, with 15 percent studying in schools that rank the lowest on California’s Academic Performance Index. But, this endemic problem of poor schools disproportionately existing in poor neighborhoods, is more about public education financing than the public education system itself.

Percentage of students in foster care, low-socioeconomic-status students, and all students in California public schools by the statewide school Academic Performance Index decile rank, 2009/10

SOURCE: WesEd

Despite these substantial barriers, there is reason to believe that we can do better.

This summer, Governor Jerry Brow,n alongside legislators from both the state Senate and Assembly, did something remarkable. They, through the haze of special interests, internecine political battles and years of bureaucratic attrition, managed to push through the most substantial overhaul to how California’s public education system is financed in a generation.

While the premise behind the “Local Control Funding Formula”, that flexibility to ever-smaller orders of government is best, may or may not prove true, the change provides for a chance at something better.

For students in foster care, a subgroup highlighted by lawmakers for special attention during this year’s public education debate, the new formula should mean stringent school-district level accountability plans that push their education forward, and robust data exchange between child welfare and education that promises research, which can guide practice.

Of course, these measures have to be implemented, and then actually work.

Until they are, students in foster care will continue to be handed an inordinate share of academic disadvantage. We know this is wrong, why it occurs and what must be done to stop it.

The challenges are substantial, the rollout of solutions incremental, and the variables complex and unpredictable.

There are two options before us. Shrug and say it’s too hard, or find that indignation to work even harder. Read the report, and decide where you stand.

Daniel Heimpel is the founder of Fostering Media Connections and the publisher of the Chronicle of Social Change.