While meditation has expanded in recent years from a zen-seeker’s path to higher consciousness to a best practice for hard-charging CEOs, it’s now gaining a foothold at a school in Southern California serving students with serious emotional and behavioral issues.

Administrators at the Five Acres School in Altadena, Calif., are testing whether meditation and mindfulness can help students succeed in the classroom. A new mindfulness program implemented there in two semesters over the past year has helped pupils stay in the classroom and minimize emotional outbursts that can derail the learning process, according to administrators.

Students at Five Acres have ended up at the school because of behavioral issues that have led them to be expelled or removed from public schools. Five Acres has contracts with 22 school districts in Los Angeles County, though most students are drawn from Pasadena Unified School District. About one in five is a foster youth who also lives at the Five Acres residential treatment center, located on campus.

Five Acres offers small class sizes and an individualized, trauma-informed approach to helping students learn how to manage their classroom performance. But crisis intervention teams at the school still need to intercede and take students out of the classroom when problem behaviors become disruptive, such as when students overturn a desk or throw an elbow at a classmate.

After the first semester in which the new mindfulness techniques were applied, Five Acres Chief Clinical Officer Rachel McClements described the results as positive. A majority of students said that the mindfulness program (known as ML2) helped them focus on classroom activities and learning. And initial data gathered by the school points to an even bigger benefit: 45 percent fewer behavior problems in the classrooms that use ML2.

“The behavioral incidents are very important to us because with them, children can’t really learn,” McClements said.

The mindfulness program at Five Acres is the brainchild of Randye Semple, a professor at the University of Southern California’s Keck School of Medicine. For nearly 15 years, she has been exploring the use of techniques associated with meditation and children in a therapeutic context.

Under Semple’s direction, the ML2 program at Five Acres is an adaptation of an eight-week meditation-related psychotherapy program aimed at adults. Since children have shorter attention spans and a less-developed ability to share abstract concepts and experiences, she designed shorter mindfulness sessions that are complemented by participatory activities.

Through these techniques, Semple hopes that meditative practices can help children manage or reduce psychological issues like anxiety and depression, often caused by earlier adverse experiences. By becoming aware of their conscious thoughts and feelings, Semple says, children can better handle their past and current negative experiences.

“The first step in mindfulness is to help them differentiate what’s going on inside them—their own thoughts, feelings, and body sensations—from what’s going around them,” Semple said. “These kids don’t have a lot in their lives that they can control, but they can choose how they respond to it.”

But while the idea of using meditative practices to help children heal from traumatic events and manage challenging behavioral issues has shown some promise, there isn’t much rigorous research to support its use in classrooms yet. That’s one reason why Semple has been studying the practices in several different school settings.

Most recently, she created the Mindfulness Matters program for the Pasadena Unified School District as a district-wide after-school program. With the ML2 program at Five Acres, however, Semple wanted to work with students who have more severe behavioral and emotional needs and examine how the ML2 program could be better integrated into a class curriculum.

She describes the latest iteration of her program at Five Acres as a hybrid of both the public school and clinical models that seeks to incorporate mindfulness practices in a more organic and sustainable way in the classroom for elementary-age children. Semple’s program was initially used in four classrooms in the spring semester, but it was extended to all seven of Five Acres classrooms for the fall semester.

While social workers helped guide participating students in the meditative practices once a week during the first go-round, in the 2015 spring semester, teachers are now tasked with integrating components of the mindfulness program into their classrooms in a way that is appropriate for the ages and developmental abilities of the students in each class.

The new arrangements allow teachers like Jason Browning to introduce the ideas associated with mindfulness to his third- and fourth-grade level class in a way that makes sense for the students.

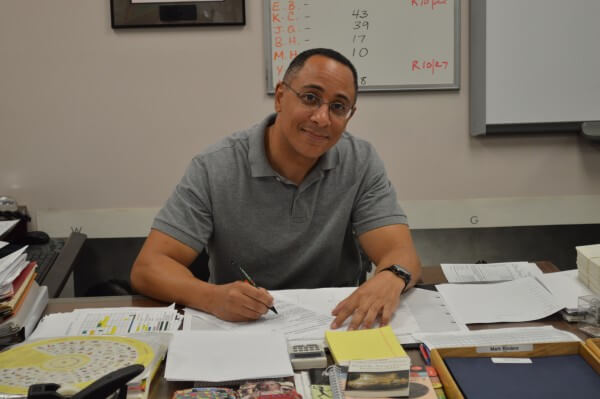

Teacher Jason Browning of Five Acres School. The school uses meditation practices to help its students regulate their emotions and behavior in the classroom.

A 16-year veteran of teaching high-needs students, Browning often starts the day by encouraging his class to slow their breathing while listening to the sounds of traditional Indian music. He tells his students to match their breaths to the beat of the music in the darkened classroom, helping them focus on the moment at hand. Other times he leads them through a few yoga poses that combine stretching and coordination with quiet concentration.

During these moments and during follow-up discussions, he’s helping his young charges build coping skills that can make it easier to deal with painful trauma and self-regulate their emotions.

“Many of these kids come from a background of negativity and trauma that they carry with them constantly,” Browning said. “Their mind is constantly occupied by it—thinking about the visit that they didn’t get from mom and dad, or the physical abuse that they experienced six months ago, or the test that I keep failing—that’s all going on simultaneously in their head.”

For a lot of students, he says, thinking about something positive or abstract is foreign or scary. For those students who have a history of abuse, even closing their eyes is difficult. A significant aspect of getting the children to participate in the ML2 program is the relationships that Browning has nurtured with the nine students in his class.

“I’m allowed to get to know them,” he said. “If there’s a problem with math or whatever we’re working on that day, the relationship with me allows them to open up about it. You have to find out where their comfort zones are, what things make them laugh.”

By building personal connections with his students, Browning is able to acknowledge the painful emotional reality that many of his students inhabit and help them deal with the resulting behaviors in the classroom, such as violent outbursts, acts of defiance and difficulty paying attention.

Browning recounts that one of his students recently erupted after the class read a story about the experiences of a young boy visiting his grandfather.

After giving the pupil some space and time, Browning discovered that the boy had been abused by his own grandfather, a detail that wasn’t included in his education plan.

For teachers at the school like Browning, the most important task is often identifying triggers, powerful emotional reminders of past trauma that often cause children to act out.

“A big part of this job is to pay attention to the triggers and to what sets them off and how to get around that, either by removing it or teaching them how to deal with it,” Browning said. “Over time, we want them to realize the idea of ‘grandpa’ is abstract without actually thinking their own grandpa is coming after them.”

Emotional disturbances are still regular occurrences in Browning’s class. But he thinks that the ML2 program gives teachers another valuable tool to help students manage their emotions and build self-esteem.

Ultimately, Browning and the administrators at the Five Acres school hope that students will gain enough control to move back into classes at public schools or special programs in less restrictive settings.

In the next few months, Semple and McClements will review the data from this past semester and determine how effective the teacher-led ML2 program has been in terms of preventing emotional meltdowns and encouraging learning.

But Browning has already seen how the exercises have given his students a better ability to solve problems even outside of the meditation sessions. Now when he sees some of his students in conflict, he asks them to take five or ten deep breaths.

The deep breathing returns them to the daily meditation exercises they’ve practiced over the past year in class and shifts their attention to the present moment.

“Now I can engage in some calm problem-solving,” Browning said. “We’re not thinking about being a ball hog, we’re not thinking about what happened at the session last night or at home; we’re just thinking about what’s going on in the present, right now.”