Since the pandemic began one year ago, foster parents across the country have gone to extraordinary lengths to support the child welfare system. An Illinois mom left her job to provide in-home childcare instead. An Oklahoma mom, caring for an immunocompromised toddler, remains housebound to protect him from the deadly coronavirus. Yet another foster parent led virtual learning for multiple children, across multiple grade levels, using only one computer.

In January 2021, Fostering Families Today, a foster, adoptive and kinship parenting magazine and partner publication with The Imprint, surveyed nearly 300 foster parents across the country to measure how their lives have been shaped by the coronavirus over the past year. Declining mental health was their most common struggle, with more than half of those surveyed listing emotional and psychological difficulties as having had a “major impact” on their lives.

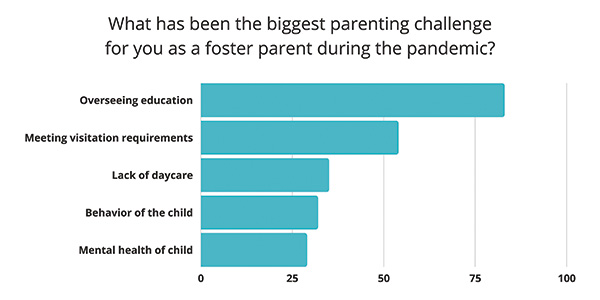

Foster parents described a loss of employment or income and a decline in their physical health as the second and third greatest impacts over the past year. More than a quarter of foster parents said that overseeing education was their biggest parenting challenge, followed by meeting the court-ordered requirements that foster children regularly visit their biological parents.

In a sign of the quiet toil of those caring for other people’s children nationwide, when asked to measure the degree to which their fostering experience has been impacted on a five-point scale, more than half of parents answered with a four or five.

Pandemic Health Struggles

More specifically, foster parents described a newfound sense of anxiety, aggravation, stress or boredom as a roadblock to their parenting.

“It’s difficult to be the best emotional support for them when the pandemic and isolation and restrictions have taken a toll on my own mental health,” one parent wrote.

Responding to a question about infection, only 8% of survey participants reported having a child in their care test positive for the COVID-19, and 15% reported that they or another adult in their household contracted the virus.

Yet many described feeling constant worry over the risk of infection. For these parents, their concern centered on children becoming exposed during in-person visits with biological family members or at school, for those whose campuses have been open.

In addition, the absence of socializing opportunities — for both parents and children alike — has contributed to loneliness and isolation. With in-person contact significantly scaled back, some parents said they feel disconnected from the foster care community or uninformed about ever-changing requirements and resources.

Vanessa Van Dyck, 44, and her husband, Amen, 47, of Long Beach, California, struggled to find support networks as first-time foster parents. “We couldn’t talk to anybody, really,” she said. “It was just us.”

Foster parent Katy McDaniel, 38, of Tulsa, Oklahoma, named socializing opportunities as the main resources her family is lacking. Her local department of health services used to host monthly meetings for foster parents prior to the pandemic, she said, but attempts at virtual meetings were limited and unsuccessful.

McDaniel, a therapist, and her wife, a foster parent engagement and recruitment specialist for the Oklahoma Department of Human Services, are seeing a rise in secondary trauma among social workers and foster parents.

“Our worker retention is going down,” she said. “We lose foster families whenever there’s no support, there’s not enough resources, we’re not giving them enough guidance and respect.”

McDaniel said she’s witnessing firsthand the trauma that children, foster parents, biological parents and social workers are experiencing from the pandemic. Since last March, despite weekly invitations to Zoom calls, her foster child’s biological mother ceased to respond, ending their contact.

“The therapist in me wonders, if there hadn’t been a pandemic, would there have been reunification?” McDaniel said. “Would she have had more time to cope and been able to change her behaviors for the better?”

Less Time, More Responsibilities

Many survey participants described a dramatic increase in their caretaking responsibilities — instead of simply being parents, they are now simultaneously teachers, daycare providers, COVID-19 safety enforcers, playmates and Zoom visitation facilitators. “Relaxation time or free time for parents and kids is all but gone,” said one parent.

More than half of the survey participants have cared for between two and four foster children since March, while a quarter have cared for only one child. About half of the children were 5 years old or younger. Almost half of the parents who responded to the survey have been fostering for one to three years, and another quarter have been fostering for four to eight years.

Daycare closures, or a lack of daycare vouchers, have forced some parents to balance full-time work with 24/7 caretaking.

Thirty-two percent of parents reported that they suffered a loss of employment or income. “Both foster parents working virtually from home with no childcare for a toddler was so stressful,” another parent shared. “We ended up taking turns caring for the child and trying to sneak in work during naptime, and then again from her bedtime to midnight.”

Catherine Nordloh, 40, of Chicago, said in the early months of the pandemic, balancing round-the-clock parenting took a severe toll on the family businesses, with her husband shifting to part-time.

“My husband and I both run our own businesses,” Nordloh said. “And the pandemic and having kids home all the time meant that I wasn’t able to work for four months — which meant that my staff became pretty much nonexistent, because we didn’t have work to pay them if I’m not working.”

Educating From Home

For 29% of survey participants, overseeing education was their single biggest challenge over the past year. “Trying to work full time and do his education was next to impossible,” one parent said. While some reported partial relief at being able to send their children to now-opened in-person schools, others are continuing to oversee virtual learning from home.

Across the U.S., state mandates for in-person and online K-12 learning vary dramatically. The vast majority of states have left in-person instruction decisions up to local-level leadership.

For parents who are caring for more than one child at a time, teaching at home is that much harder. One parent wrote, “When school shut down in March, I had a 6th grader who could not read above a 2nd grade level. I had to try to keep the kids separate so they would not fight, and read all assignments to this 6th grader and help her write answers. We could only obtain one computer, so the kids had to share it to do their schooling.”

A few survey participants said while they’ve shifted to homeschooling, they’ve also had to draw on personal finances to pay for additional tutoring and educational programs.

With the absence of structure normally provided by school and the added stress of pandemic-related isolation, many parents reported seeing regression in their child’s behavior. For a few parents, these setbacks resulted in the child being moved to a group home.

One reported that there have been no visits since her foster child moved to residential group care. Another said her child’s increased Xbox use became both a blessing during isolation and a contributor to a “major meltdown and ultimate removal from our home after he had made tremendous progress in his behavior.”

Another survey respondent shared the feelings of foster parents spread across the U.S. during the pandemic, noting: “I have a hard time getting the kids ready for school, they don’t want to do it, they want to go out to eat, play and be around other people. Their behavior is getting worse, as they get more comfortable in the home, and visits with Mom are giving them false hope of seeing in person, so old behavior is coming out.”

Coronavirus Exposure

For families who tested positive for the coronavirus, subsequent arrangements varied. Some were able to self-quarantine in a bedroom and rely on a spouse or other family member to care for the children. Many temporarily paused in-person visits in addition to quarantining for two weeks. Only one parent reported receiving additional resources and check-in phone calls from an agency.

“I am just recovering from COVID, and I’m just currently exhausted,” one parent shared. “It’s almost more than I can handle to get through each day. But I’m doing it.”

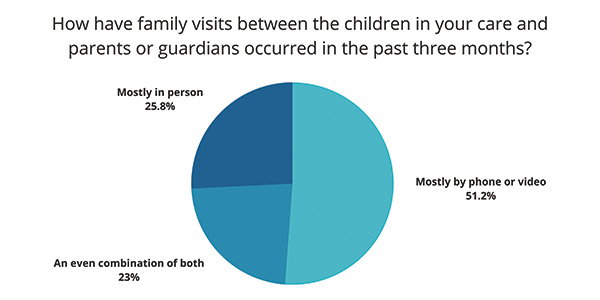

Half of the survey respondents said they have been conducting visitations mostly by phone or video, while a quarter have hosted mostly in-person visitations and a quarter have done an even mix of both. Many parents expressed tension with feeling pressure to participate in in-person visits. One parent said their attempts to express safety concerns with their local child welfare department were ignored. Another struggled with navigating mask-wearing agreements and federal safety guidelines with biological family members.

“I fully understand the importance of visitations. But we are essentially opening up our homes fully to the virus,” one parent wrote. “We have zero control over the precautions that the bio family is taking and how exposed they are. And then we are forced to be exposed. I can’t keep my family (who has immuno issues) safe and that’s absolutely terrifying.”

McDaniel’s worries that for her young foster son, coronavirus limitations are impacting his development.

“He’s a toddler, and this is the time when they experience the world as it is and learn new things,” she said. “He has a weakened immune system, and so we are unable to take him anywhere.”

Some parents expressed a desire for receiving the coronavirus vaccine, to protect against unpredictable exposure. “I sort of feel like a first responder,” one parent wrote.