Amid a thunderous beating of red animal-skin drums and powerful song, survivors of Indian boarding schools met in southern Oklahoma this morning with the nation’s ranking official in charge of strengthening tribal self-determination in Indian Country and upholding the government’s treaty obligations to tribes.

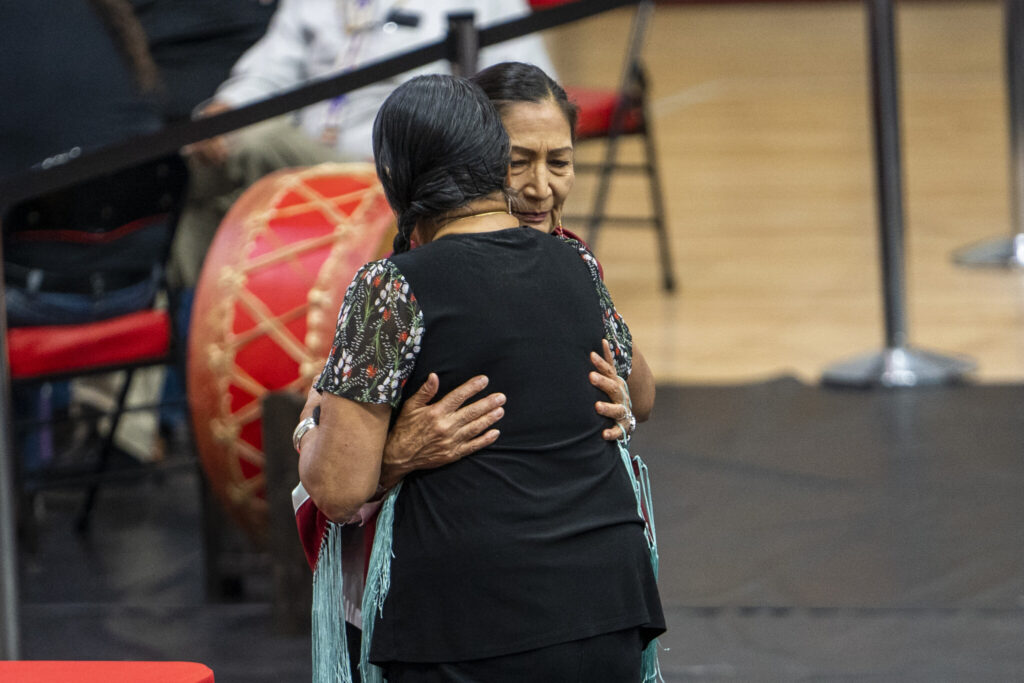

Hundreds of former students and their descendants had come to give testimony about the legacy of Indian boarding schools. But first, a dancer in a tasseled buckskin dress and feathers moved among those gathered in a rural gymnasium filled with women in colorful ribbon skirts and men in crisp, plaid button-down shirts. Then, they stopped to pray with Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, a descendant of the schools that have haunted so many Native American families over centuries.

Today’s meeting in Caddo County marked the first stop on Haaland’s year-long Road to Healing Tour, in a region ringed by the Gypsum Hills, the Red Bed plains and the Wichita Mountains.

“I want you all to know that I am with you on this journey, and I am here to listen. I will listen with you, I will grieve with you, I will weep you with you and I will feel your pain,” said Haaland, a Laguna Pueblo member from New Mexico and the nation’s first Indigenous cabinet secretary. “As we mourn what we have lost, please know that we still have so much to gain. The healing that can help our communities will not be done overnight but it will be done.”

Responding to the historic address, Delores Twohatchet, who is Kiowa and Comanche, stood with hands shaking. She pressed a burgundy and teal shawl, as a gift, into Haaland’s hands.

One boarding school survivor came from Michigan to attend: Bruce Charles Lachniet, who is Ottawa-Chippewa and a former stagehand for musical legends Cher and Elton John.

In an interview before the formal testimony began, Lachniet, 63, told The Imprint he’d come to have his voice heard after failed attempts over the past two years to contact the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the president and the Department of Interior.

The horrors of boarding schools are increasingly well known, and they are in the process of being documented by Haaland’s cabinet. But each account of lived experience — and the ripple effects throughout families and tribes — is searing.

Lachniet said he’s here because he wants to know why nothing has been done about the treatment he’s long tried to report to authorities. As a boarding school student and the son of a boarding school survivor, he and his mother have experienced the unthinkable. She was doused with DDT, a powerful chemical agent that burns skin and causes vomiting, tremors, shakiness and seizures. His own horrific experience began when he entered a Catholic school in Michigan, he said. His hair was forcibly cut and he recounted being molested as young as 6 years old, at one point sexually assaulted with a broom.

And when he reacted to the vicious attacks on him and broader attempts to crush his people, Lachniet said he was beaten.

As an adult, he said he doesn’t even want to claim his legal last name because “my real name, my Indian name, Mick-Saw-Bay, was stolen from me.”

A ‘Trauma-informed’ Tour

Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs Bryan Newland, a citizen of the Bay Mills Indian Community, a tribe consisting of Ojibwe or Chippewa people, accompanied Haaland on today’s Road to Healing Tour. The nationwide tour aims to elicit testimony from boarding school survivors and their descendants within their own communities, creating a permanent oral history from first-person accounts. “Trauma-informed support” was made available during the Oklahoma event and will be provided throughout the year-long, multi-state tour that will include stories from survivors, transportation assistance for those who wish to attend, and follow-up support available upon request.

Future stops will be in Hawaii, Michigan, Arizona and South Dakota, with more tours to come in 2023, according to the Interior Department.

The survivors’ experiences echo Haaland’s own history as the granddaughter of boarding school students and the great-granddaughter of a man sent to the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania, almost 2,000 miles from his tribe. That school’s founder Richard Henry Pratt is notorious for his oft-repeated pitch for forced cultural assimilation: “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.”

“Federal Indian boarding school policies have touched every Indigenous person I know. Some are survivors or descendants, but we all carry the trauma in our hearts,” Haaland pronounced today from the Riverside Indian School gymnasium in Anadarko.

Before she headed into a private session with roughly hundreds of survivors and their descendants, Haaland addressed roughly two dozen reporters today, stating: “My ancestors endured the horrors of the boarding school assimilation policies carried out by the same department I now lead. This is the first time in history that a cabinet secretary comes to the table with this shared trauma.”

Shedding light on troubled history

Opened in 1871 by Quaker missionaries, Riverside is the nation’s oldest boarding school operated by the federal government. It is one of the 408 across the U.S. identified in Haaland’s recently launched Federal Boarding School Initiative — described by the Department of the Interior as the government’s first comprehensive attempt “to shed light on the troubled history of Federal Indian boarding school policies and their legacy for Indigenous Peoples.”

Haaland has pledged to document the schools’ troubled pasts, address their intergenerational impact and fully account for the trauma they inflicted throughout Indian Country.

In May, the Interior Department released its initial accounting of Indian boarding schools in this country, which first opened in 1801 with the failed intention of obliterating Native identity and forcing assimilation into the dominant white society. The ground-breaking report launched by Haaland, the nation’s first Indigenous cabinet secretary, also began documenting the schools’ horrors, identifying 53 marked and unmarked burial grounds on school sites where American Indian, Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian children were forced to attend for over a century. The inquiry has so far accounted for 500 child deaths across 19 schools, with family members rarely notified.

Roughly half the schools were supported by the federal government, but operated by Christian institutions that attempted to eradicate the cultural and religious practices of America’s First Nations. Boarding schools were most heavily concentrated in Arizona, New Mexico and Oklahoma, where there have been 76 Indian boarding schools, according to the Interior Department.

Federal archives show that the U.S. government “coerced, induced, or compelled Indian children to enter” the schools where their treatment included “solitary confinement; flogging; withholding food; whipping; slapping; and cuffing.”

In a parallel process, a bill now moving through Congress would establish a Truth and Healing Commission on Indian Boarding School Policies in the United States. The legislation — given preliminary approval by a congressional committee last month — would include tribal members, mental health experts and representatives from numerous national Indigenous organizations.

The bill is sponsored by Democratic Rep. Sharice Davids of Kansas, a member of the Ho-Chunk Nation. If enacted, a 10-member commission appointed by the president and leaders in both houses of Congress would hold public hearings with Indian boarding school survivors and document “the impacts of the physical, psychological, and spiritual violence” they suffered.

The U.S. efforts to acknowledge and repair the harm from its centuries-long practices trail well behind its neighboring nation to the north. The efforts toward healing from traumatic boarding school experiences began in Canada in 2006, when its prime minister apologized to that country’s First Nations. In 2015, Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission released a seven-volume report describing terror-filled experiences in its schools of forced attendance. In January, Canada settled with tribes for $31.5 billion — the largest such award in the country’s history — for the government’s violent policies of family separation. The money will reform the child welfare system and compensate Indigenous families whose children were unnecessarily removed from their homes and taken into foster care.

Meanwhile, this month, the Federal Court of Canada certified a class-action lawsuit against the government on behalf of Indigenous children who were removed from their families and placed in non-Native homes. The suit alleges the government’s actions showed “systemic negligence” toward Indigenous children within Canada’s child welfare system.

Survivors in Caddo County speak out

Beginning in the 1800s, students were wrenched from the Wichita, Delaware and Caddo tribes and sent to Oklahoma’s Riverside school. This went on for about half a century, and in 1922, the school began removing Kiowa students from their homes as well. Navajo or Diné children from Arizona and New Mexico were sent there beginning in 1945.

Today, the school is described as a far cry from its past. It currently serves 800 students from 75 tribes for nine months of each year and is operated by the Bureau of Indian Education. The school is described as providing a holistic education, with an academic focus and access to technology in addition to respect for students’ cultural and spiritual practices.

But the trauma of the past is ever present.

Desiray Emerton, a Seminole Nation council member and military veteran, brought her adult daughter Krystal to the Road To Healing tour stop. She said it’s important for her daughter to know that the systemic social, health and political problems of Indian Country began with the treatment of students at boarding schools.

This event is an opportunity for therapy and healing, she said, and a time for action.

“We just want the truth, we’re not trying to blame anybody,” Emerton said. “We just want to make sure that our history is being told. We want the truth known so we can begin to address the healing process.”

Emerton, 52, said her mother and grandmother were boarding school survivors, attendance that had lasting effects throughout her childhood, including difficulty bonding with the family’s matriarchs. Her grandmother attended Goodland Academy in Choctaw County, and other relatives attended Chilocco Indian School in north-central Oklahoma. Due to the generational impact of abusive treatment at boarding schools, she said, “my mother told me that she had to learn how to be compassionate with me.”

Because her foremothers were part of a “discrimination that’s nationwide,” they were often beaten for using their language, or for speaking when not spoken to.

“Boarding schools did that and they took so much from Indigenous communities,” Emerton said. “My mother’s mother didn’t know how to show love or cuddle her due to the sterile environment and harsh treatment at Goodland.”