In 2002, lawyers representing foster youth in Los Angeles sued the county and California over its failure to service the mental health needs of children in or at risk of entering foster care. For years the mental health issues that these vulnerable children face were often ignored. The children who did receive treatment were frequently hospitalized when outpatient services would have sufficed.

Twelve years later, the clock has nearly run out on the settlements that stemmed from Katie A. v Bonta. On December 1, 2014, separate court settlements with the state and Los Angeles County could end.

Following is The Chronicle’s analysis of what has happened since the settlement and where the state and Los Angeles could go next with regard to providing quality mental health services to children in need.

How We Got Here

In 2002, Los Angeles County and the state of California became ensnared in a federal lawsuit. Lawyers represented a handful of children and youth, alleging massive gaps in mental health care services available to children in the child welfare system.

These children were either in foster care or at risk of placement into foster care due to a maltreatment report. Katie A., the lead plaintiff, had never received therapeutic treatment in her home. By age 14, she had experienced 37 separate placements in Los Angeles County’s foster care system, including 19 trips to psychiatric facilities.

Evidence strongly suggests that children in foster care deal with significant mental health issues at a much higher rate than the community at large. One study showed that foster youth in California experienced mental health issues at a rate two-and-a-half times that of the general population.

Los Angeles County settled with the plaintiffs in 2003 and accepted the oversight of an advisory panel. After years of litigation and negotiation, the state came to terms only in 2011. A “special master” was appointed to oversee compliance efforts.

The requirements are the same for both Los Angeles and the state, and they apply to certain children and youth who are in or at risk of entering foster care. These children are identified as the “Katie A. subclass.”

Eligibility for the subclass is tricky to explain. First, a youth absolutely has to be fully Medicaid-eligible, and meet the criteria for specialized mental health services set by the state. He or she would also need to be in foster care, or be at risk of entering foster care, because of a maltreatment investigation.

There is another hurdle. A youth can only be considered part of the subclass if one of the following two things is true:

- A system is considering wraparound or specialized services for the child

- A child is currently hospitalized for a behavioral condition, or has been hospitalized three times in the past 24 months for behavioral issue

If a youth meets all those criteria, the settlement mandates that counties adhere to a “core practice model” for screening and treating foster youths. This must include the following specified services:

- Intensive Care Coordination: targeted case management that starts with assessment and moves through treatment plans.

- Intensive Home-Based Services: the provision of mental health treatment in a child’s foster or biological home.

- Therapeutic Foster Care: foster homes specially trained to meet the needs of children and youth with serious mental health challenges.

The Numbers, So Far

So how is it going? In essence, the settlement is about determining which children entangled with the child protection system have mental health needs, and then giving them appropriate treatment. The court is measuring progress on several counts, including these three critical points:

- How many members of the Katie A. subclass are identified.

- How much money was spent assessing and treating those subclass members. (Most of this is Medicaid spending, with the exception of Therapeutic Foster Care, which is not yet an allowable Medicaid expenditure.)

- The levels of Integrated Care Coordination (ICC) and In-Home Based Services (IHBS) that have been provided.

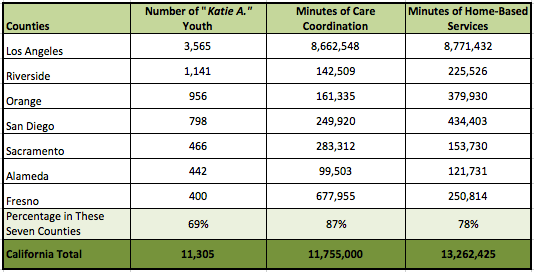

The statewide numbers show clear increases on all counts. There were 11,305 members identified in the Katie A. Subclass during the most recent yearly report, released in October, an increase from 10,314 in the previous year. Spending on mental health assessment and services for these youths reached $97.1 million, a nine percent increase from the year before.

Far more of that money was spent on ICC and IHBS, the service models demanded by the settlement. The number of ICC minutes provided is up 50 percent to 11.8 million; IHBS minutes are up 58 percent to 13.3 million.

When one drills down to the county level, it becomes evident that the implementation has been uneven. Two very lowly populated counties, Alpine and Tehama, did not report a Katie A. Subclass at all.

Fourteen counties, including Santa Clara, had their data suppressed in the report “to protect patient privacy.” Those counties identified a total of 84 subclass members.

An additional ten counties did identify members of the subclass, but provided no intensive home-based services to them. There were 457 subclass members combined in those counties.

On the other side of the equation, a lot of Katie A. action occurred in a few places. Six counties – Alameda, Fresno, Orange, Riverside, Sacramento and San Diego – account for 54.3 percent of Katie A. Subclass members.

It is hard to imagine that more than half of the California youths who qualify under Katie A. are in just those six counties. According to Chronicle calculations based on 2013 and 2014 data, these six account for about 26 percent of California’s abuse and neglect allegations, and 41 percent of its foster youth population.

Breakdown of Katie A. youth, care coordination and home-based services in seven California counties.

Nearly a third of all children and youth counted as part of the Katie A. Subclass were identified by Los Angeles County. Those 3,565 children received two-thirds of all the Intensive Home-Based Services provided to subclass members in the state.

But while Los Angeles’s ratio of IHBS minutes per Katie A. Subclass member dwarfed every other county, it spent far less on each youth. L.A. County spent a total of $27.5 million on 3,565 youths, or $7,700 per youth, according to The Imprint’s calculations.

Compare that with Alameda County, which identified 442 Katie A. Subclass members and spent just under $10 million to serve them, nearly $22,500 per youth.

The numbers suggest that, clearly, Katie A. had some impact on the state as a whole, and that much of that impact took place in a handful of large counties.

Tomorrow, we go beyond the numbers, asking experts and lawyers who litigated the case what’s happened since the 2011 settlement, and what’s next.

Note: This story was updated on Nov. 1 to more precisely define the Katie A. Subclass eligibility

John Kelly is Editor-in-Chief of The Imprint. Reporter Jeremy Loudenback also contributed to this story.